Spatial UI controller

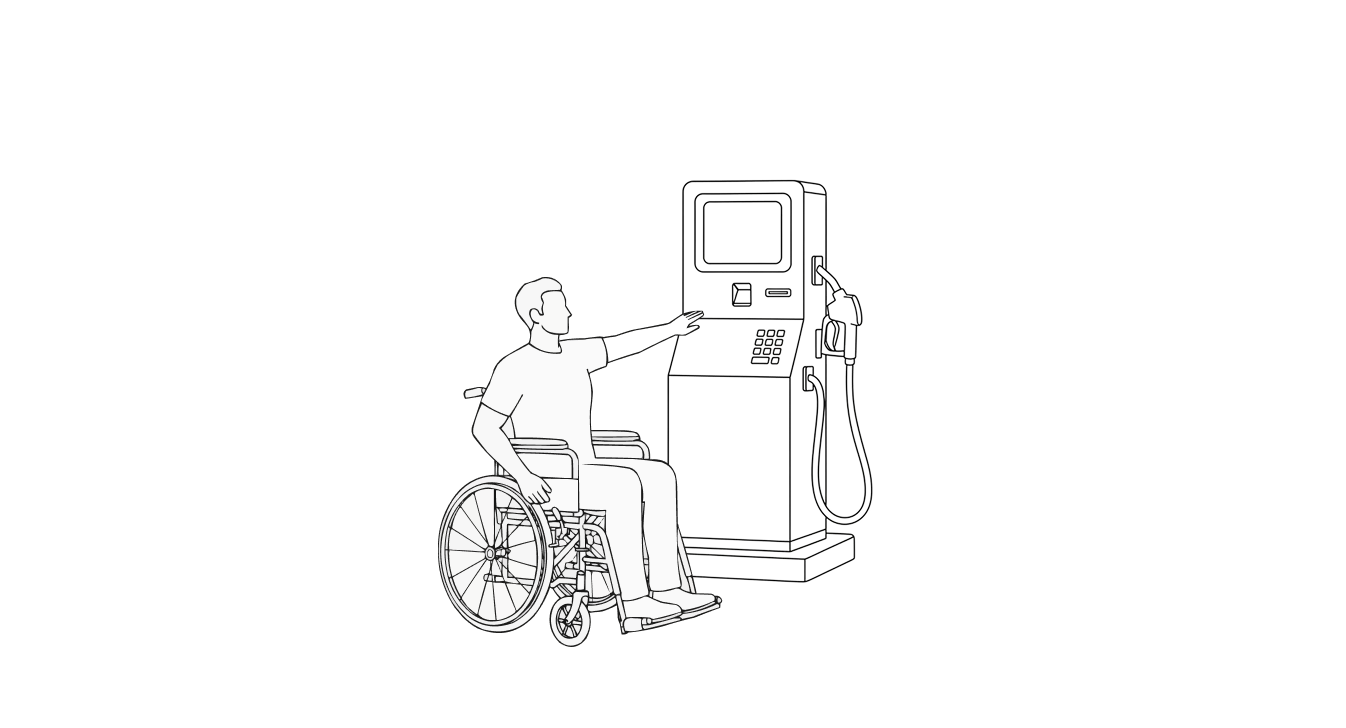

Make gas station displays accessible to paraplegic users through spatial interactions.

1 - Context

In the world of fuel stations, accessibility has always been a rather unclear concept for hardware manufacturers. The idea that a person in a wheelchair could refuel their vehicle completely independently—without the assistance of another human being—was considered almost utopian.

From this problem, I decided to explore the field of spatial interfaces and imagine how these tools could be applied to real, everyday issues.

Today, accessibility in physical interfaces often relies on modifying portions of the screen, compressing components or functionalities, and sometimes completely redesigning the software’s UI.

This creates a burden especially for developers, who need additional effort, time, and therefore cost to build a separate version of the software (which often never gets developed) just to accommodate segments of users with disabilities.

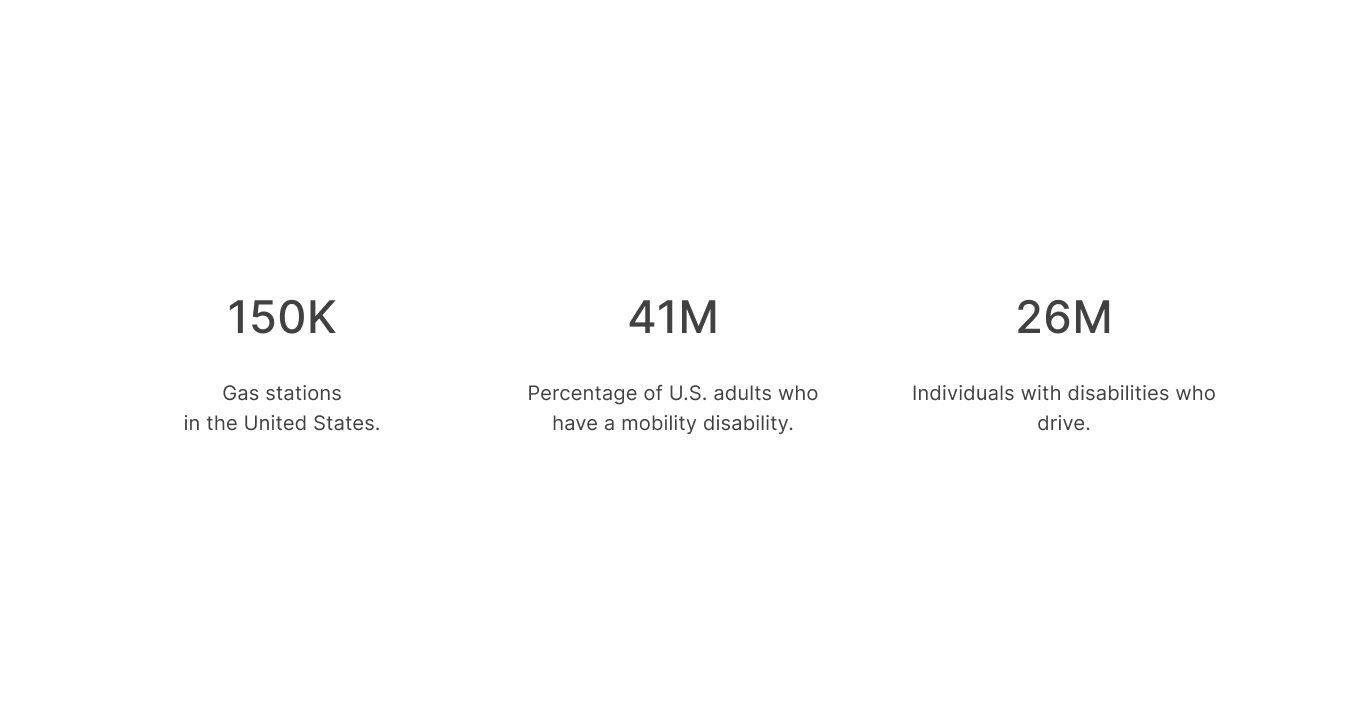

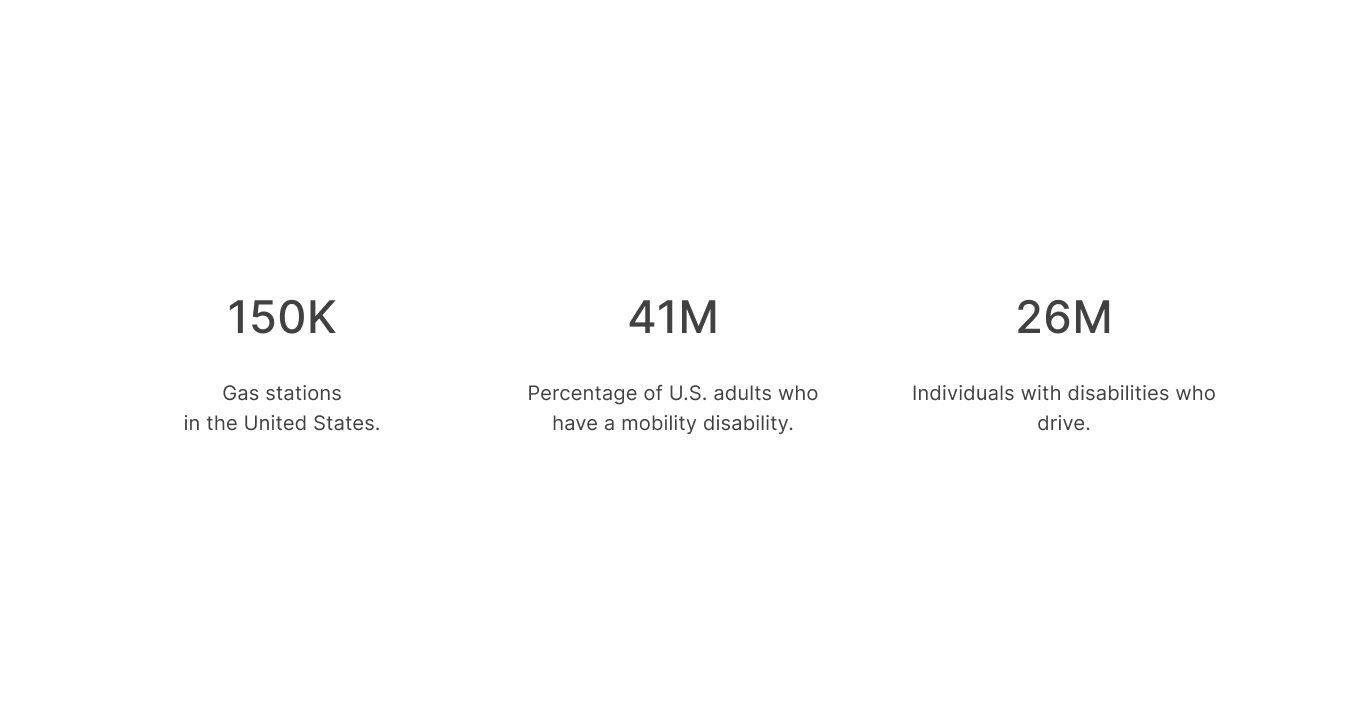

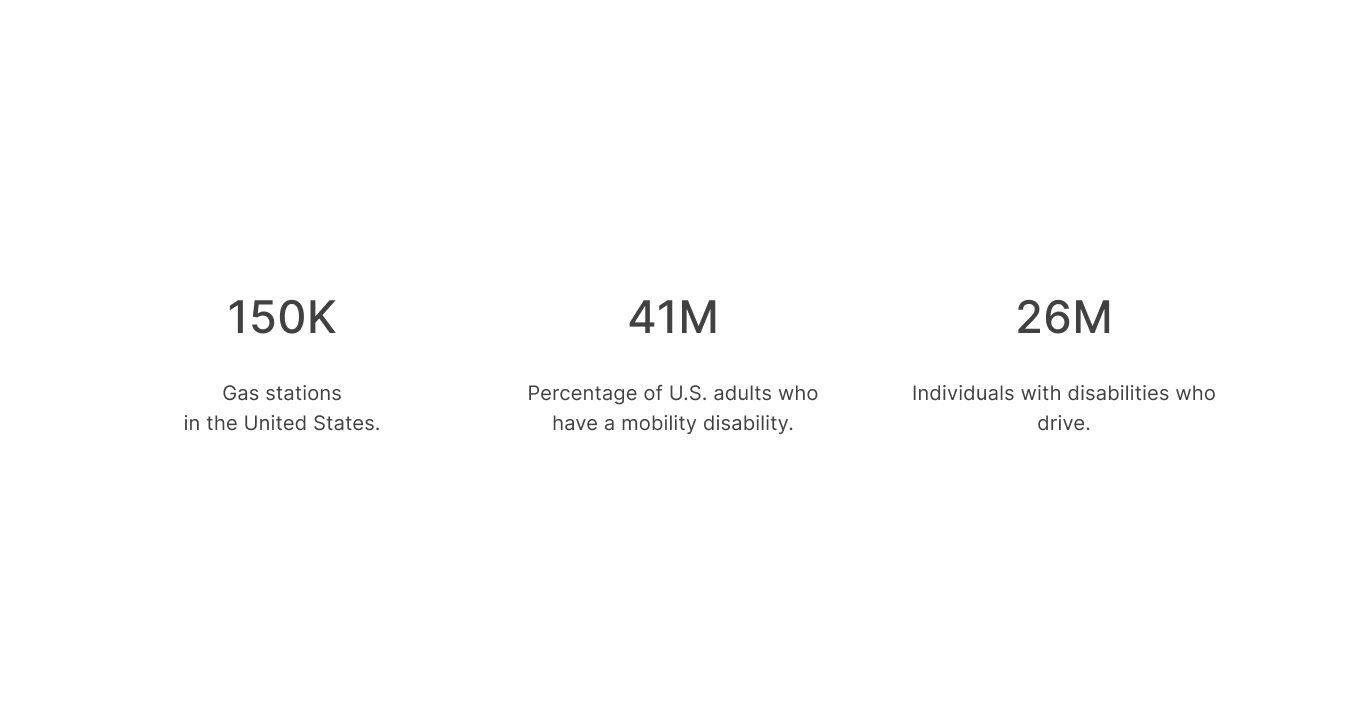

People with disabilities can drive, but how many are there?

In the United States, about 65% of people with disabilities drive.

In this case study, I focus on paraplegic individuals rather than quadriplegic ones, since the latter, being unable to use the upper part of their body, are generally not able to operate a vehicle. Paraplegic people, on the other hand, can often maintain a reasonable level of autonomy—when the conditions allow it.

Overall, around 65% of people with disabilities drive a car or other motor vehicle, compared to 88% of people without disabilities. On average, drivers with disabilities drive 5 days a week, while those without disabilities drive 6 days a week.

Can people with paraplegia drive a car?

In a broader national survey conducted in the United States, 36.5% of all individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) drove a modified vehicle, with paraplegia being a significant predictor of driving ability.

The study included a total of 160 participants. Overall, 37% of individuals with SCI drove and owned a modified vehicle.

Nearly half of the people with paraplegia (47%) were drivers, while only 12% of those with tetraplegia drove.

Data Resource: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29288252/

The majority (93%) of drivers were under 60 years old and had a higher level of independence in daily living activities. More drivers (81%) than non-drivers (24%) were employed; drivers also reported better community reintegration and overall quality of life.

The three most common barriers to driving were medical reasons (38%), fear and lack of confidence (17%), and the inability to afford vehicle modifications (13%).

2 - Problem

People with disabilities encounter significant barriers when interacting with public interfaces such as fuel pump displays, ticket machines, ATMs, and self-service kiosks.

These systems are typically designed around the physical reach, posture, and motor capabilities of an able-bodied user—leaving wheelchair users and individuals with reduced upper-body mobility at a clear disadvantage.

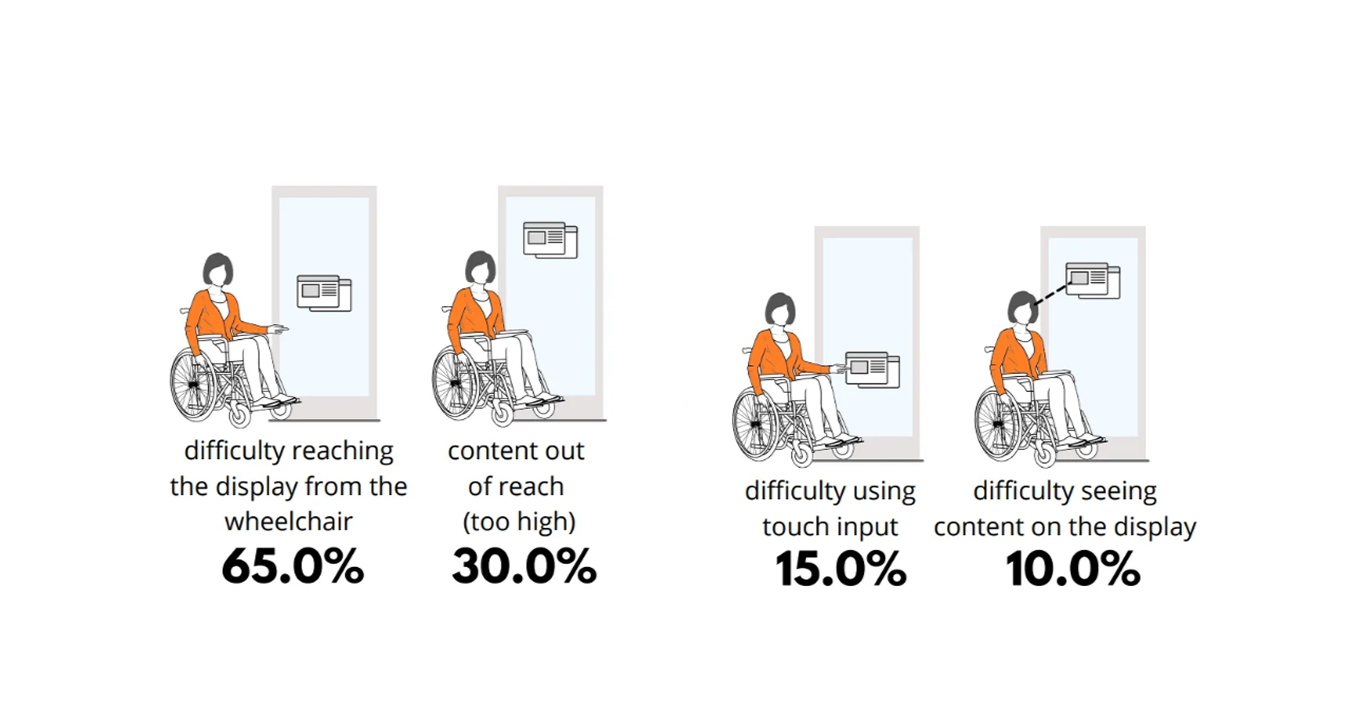

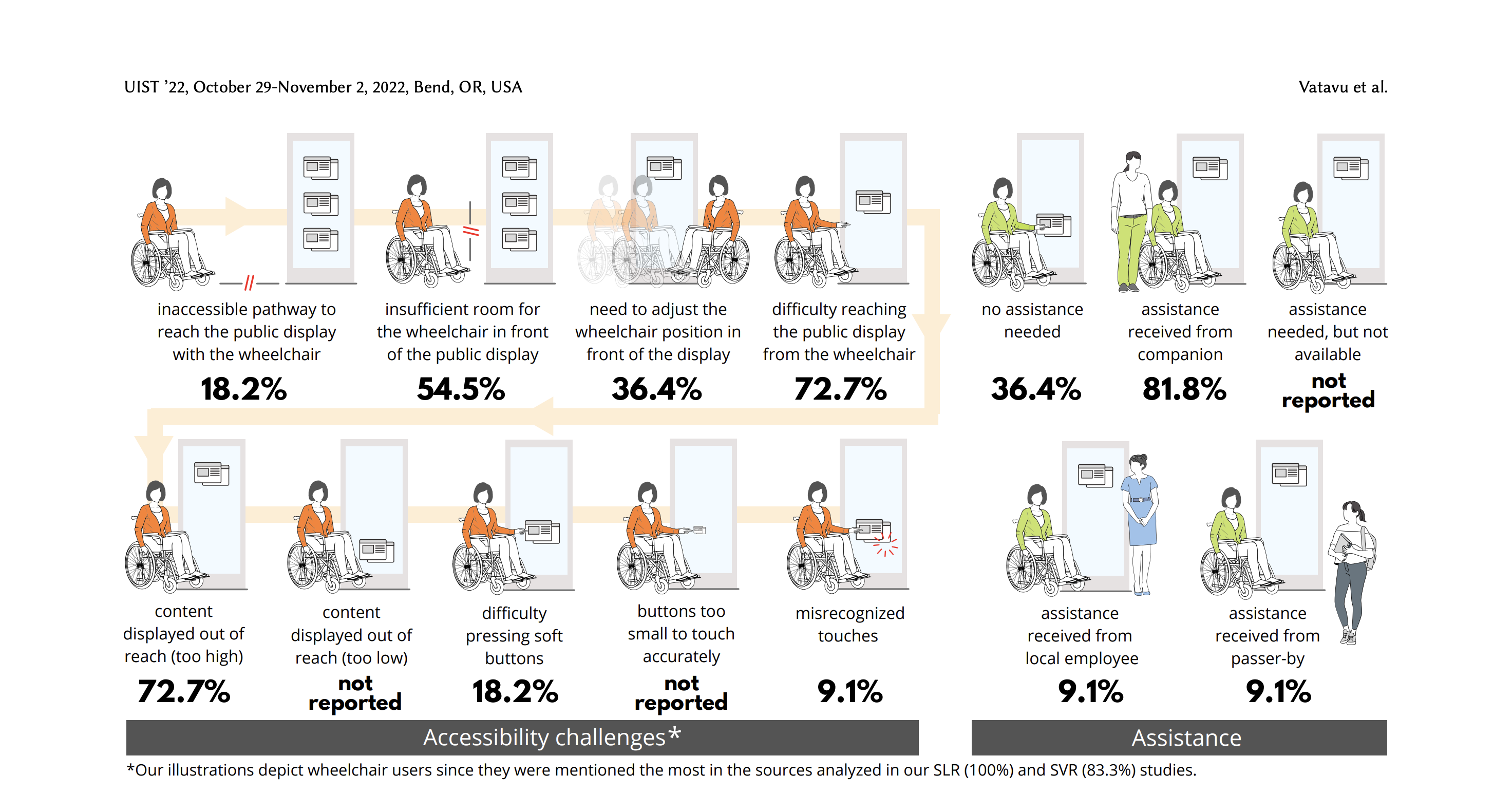

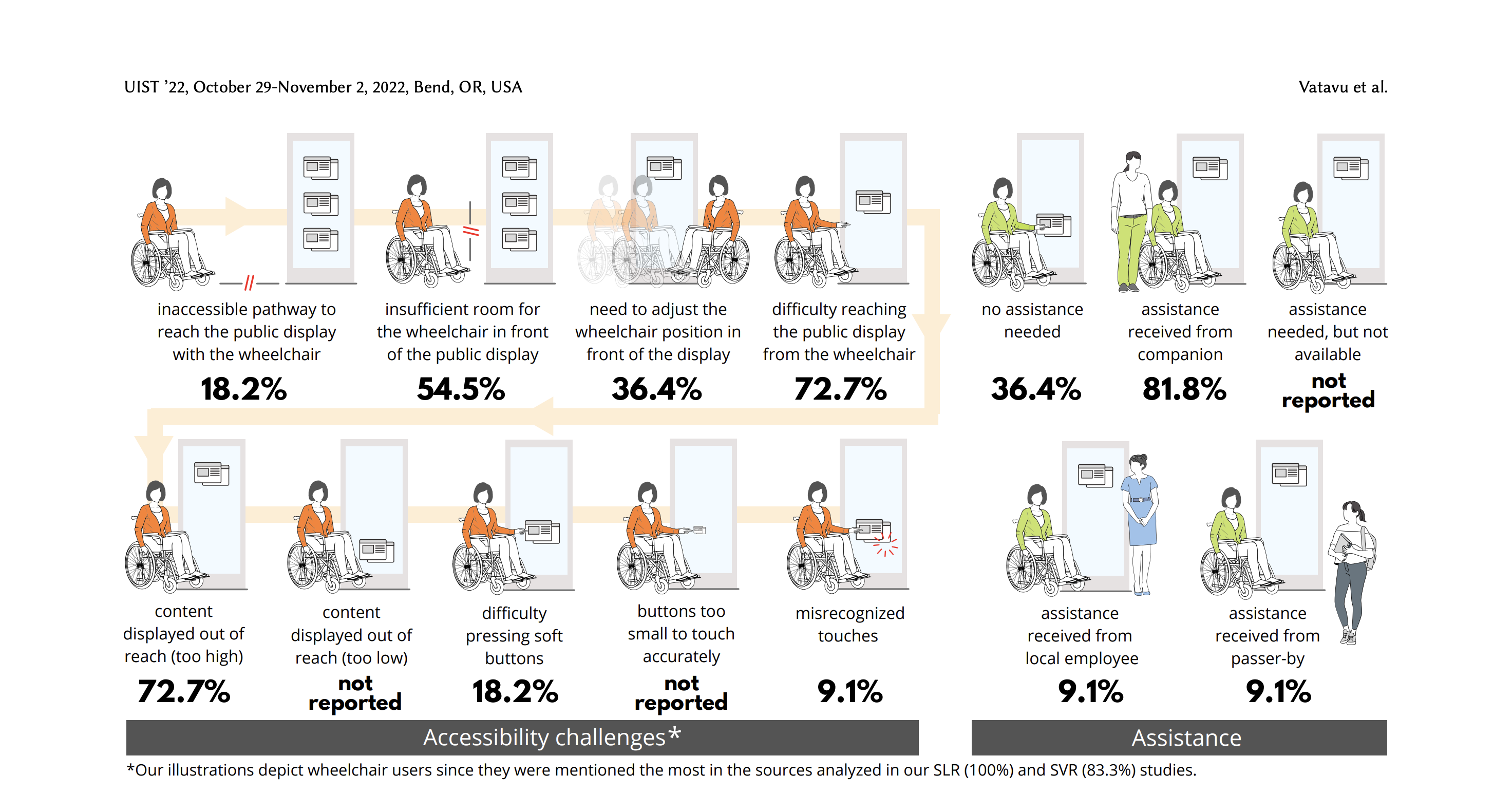

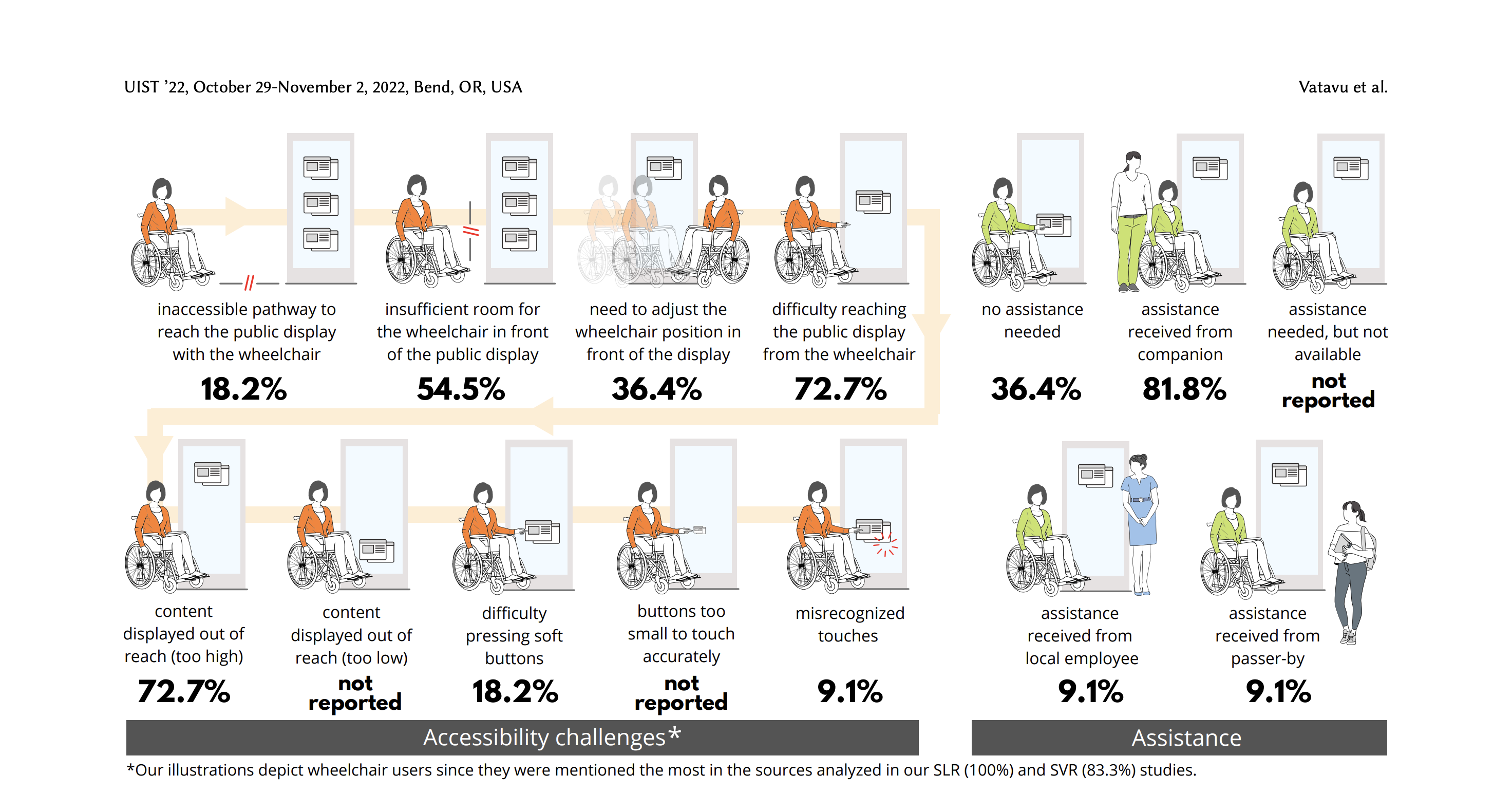

This study https://mintviz.usv.ro/publications/2022.UIST.pdf involved eleven participants (nine men, two women), aged between 28 and 59.

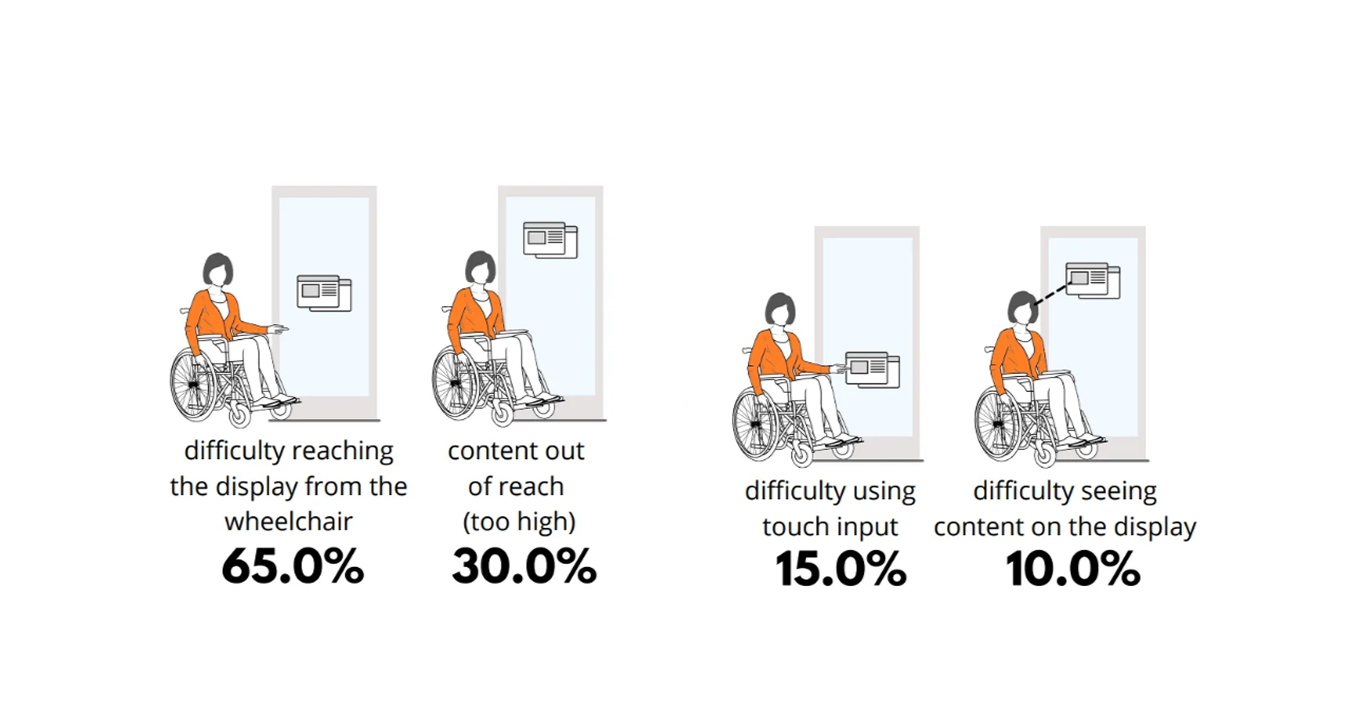

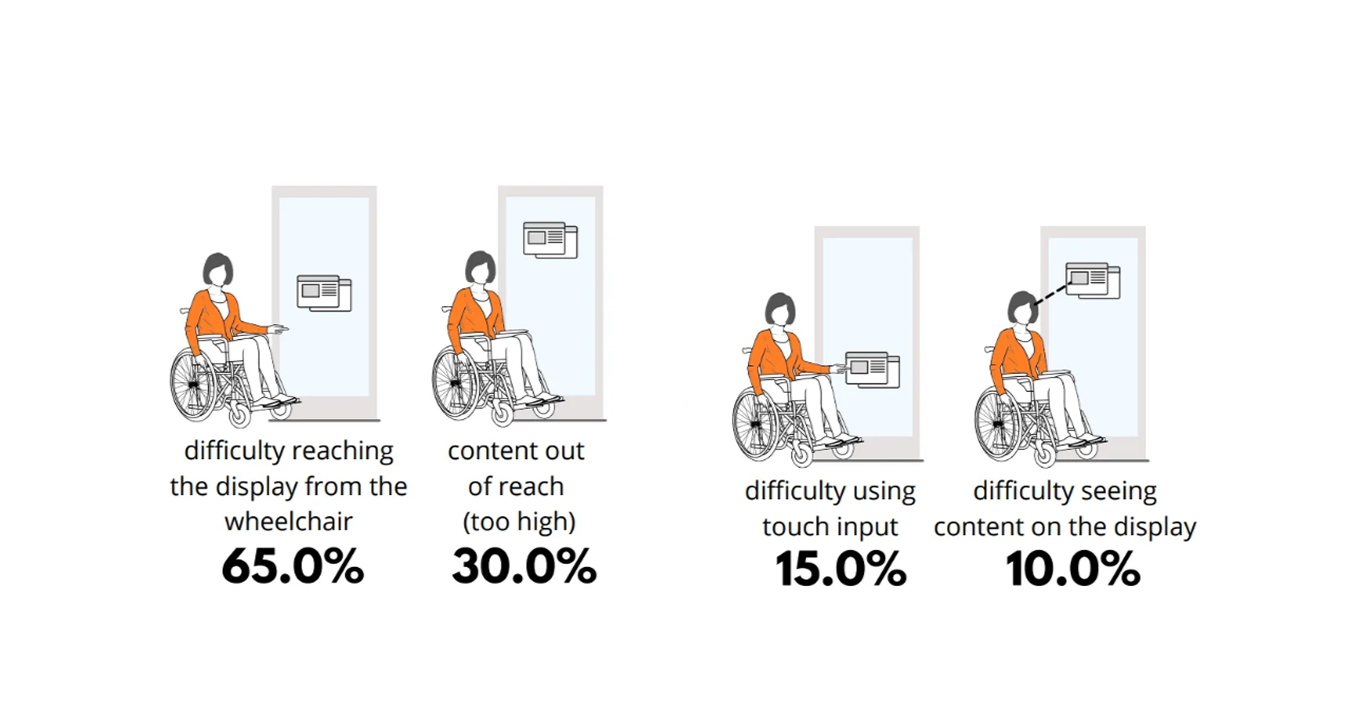

65% difficulty reaching the display from the wheelchair

Two primary accessibility challenges emerged for wheelchair users when interacting with public displays:

- Reaching content placed too high on the screen, making it physically difficult or impossible to access.

- Precisely selecting on-screen targets via touch input, due to small touch areas and the precision required.

3 - Approach

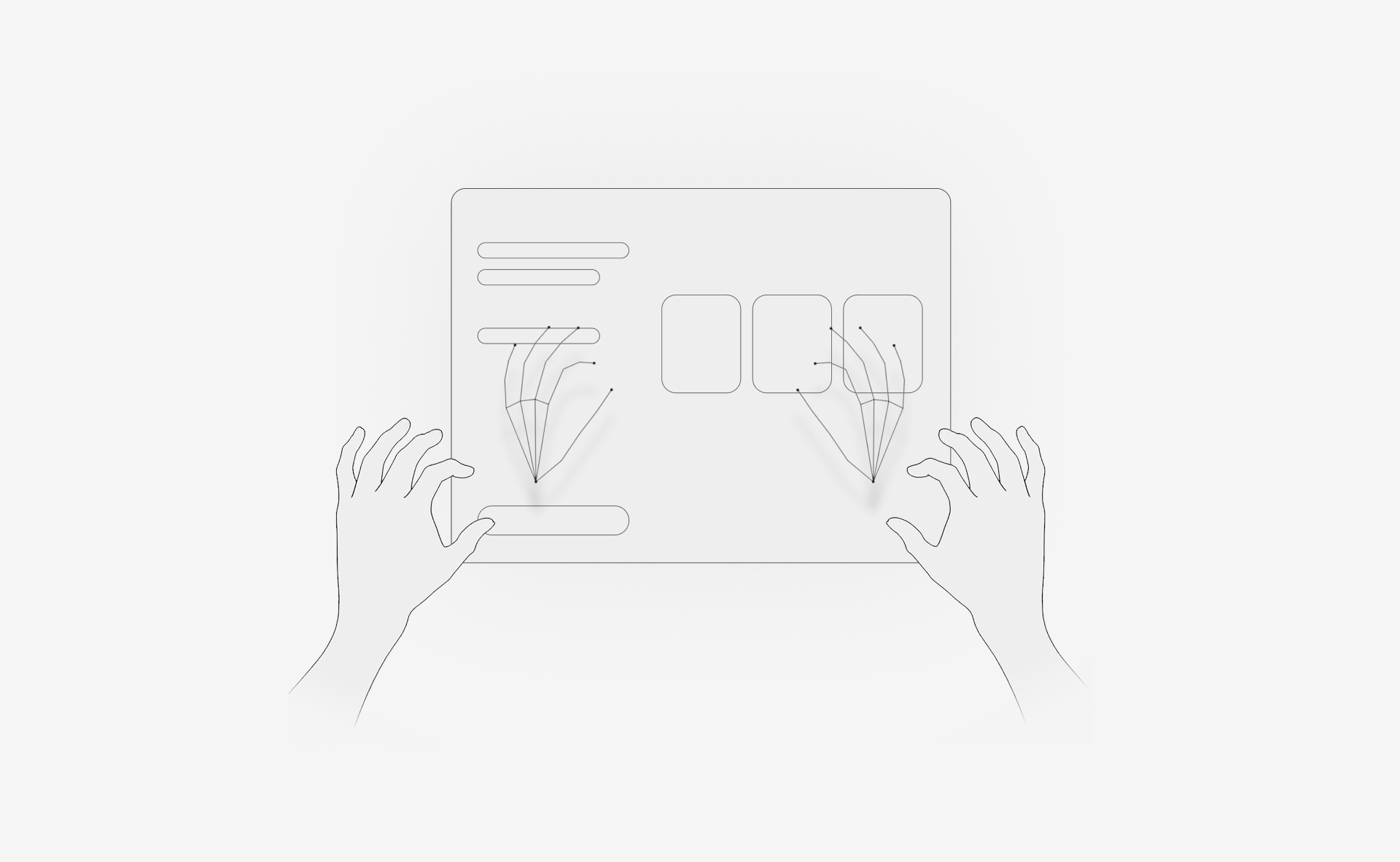

To implement the core functionalities, I began by studying the main guidelines for spatial interfaces and extracting only the principles relevant to this specific type of interaction.

Certain traditional components—such as physical or on-screen keyboards—are rarely essential in fuel dispensing or EV charging workflows, and therefore can be omitted in favor of more streamlined interactions.

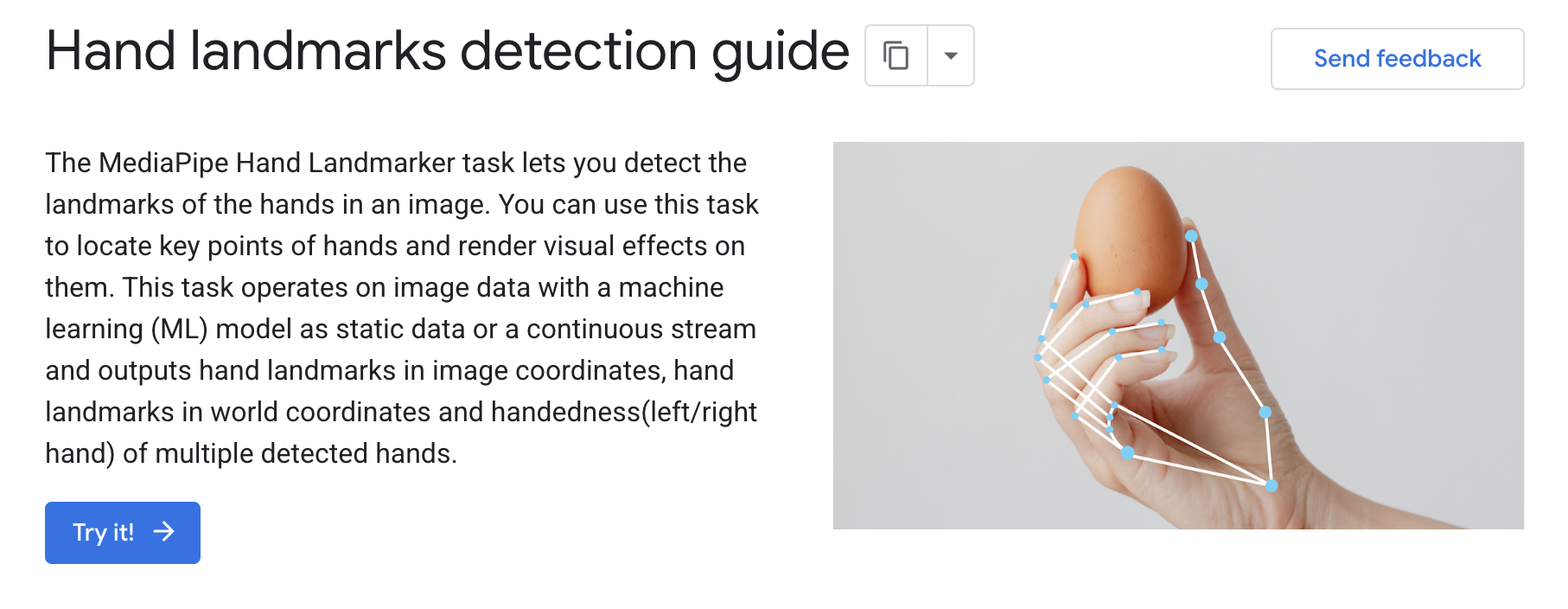

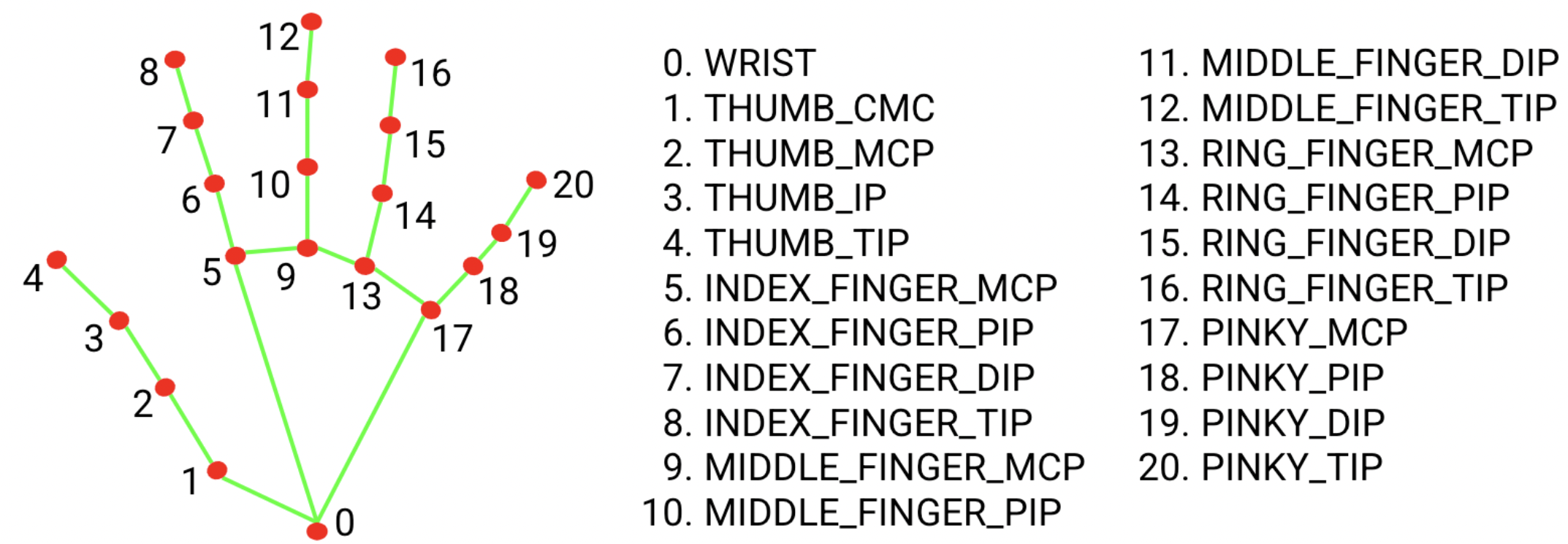

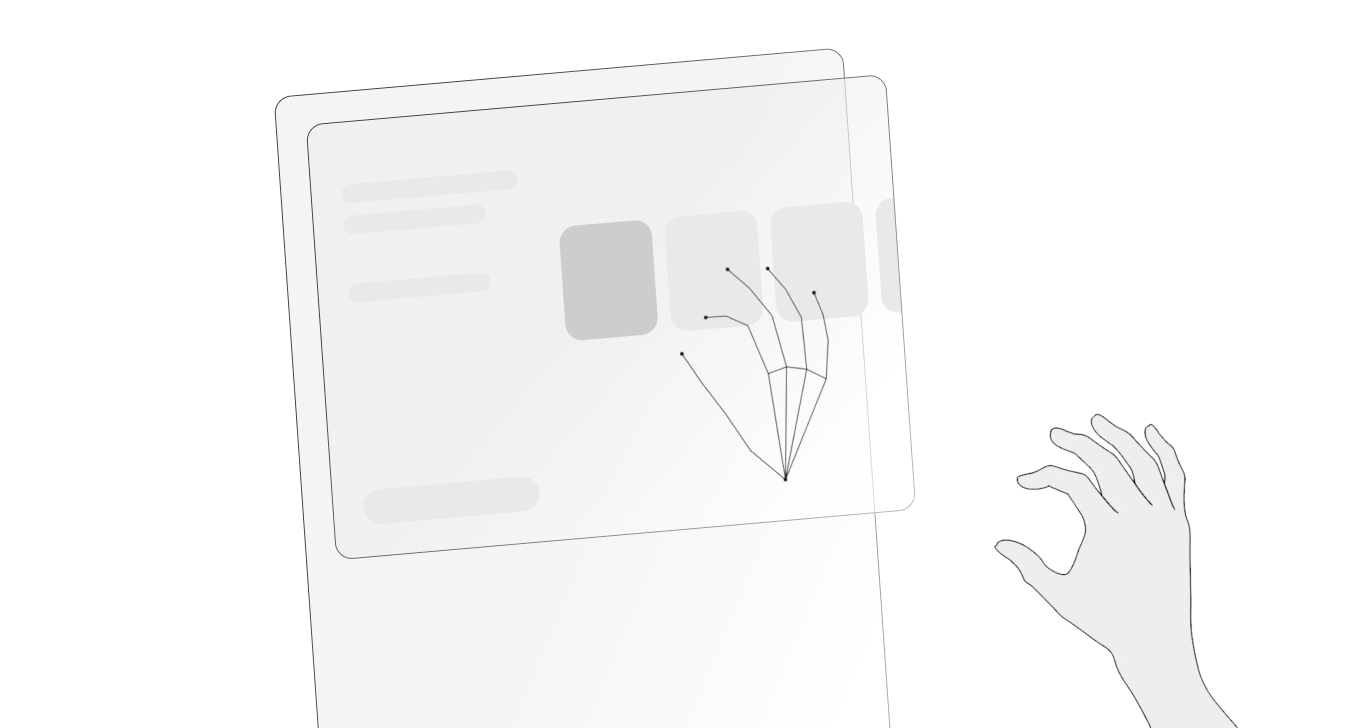

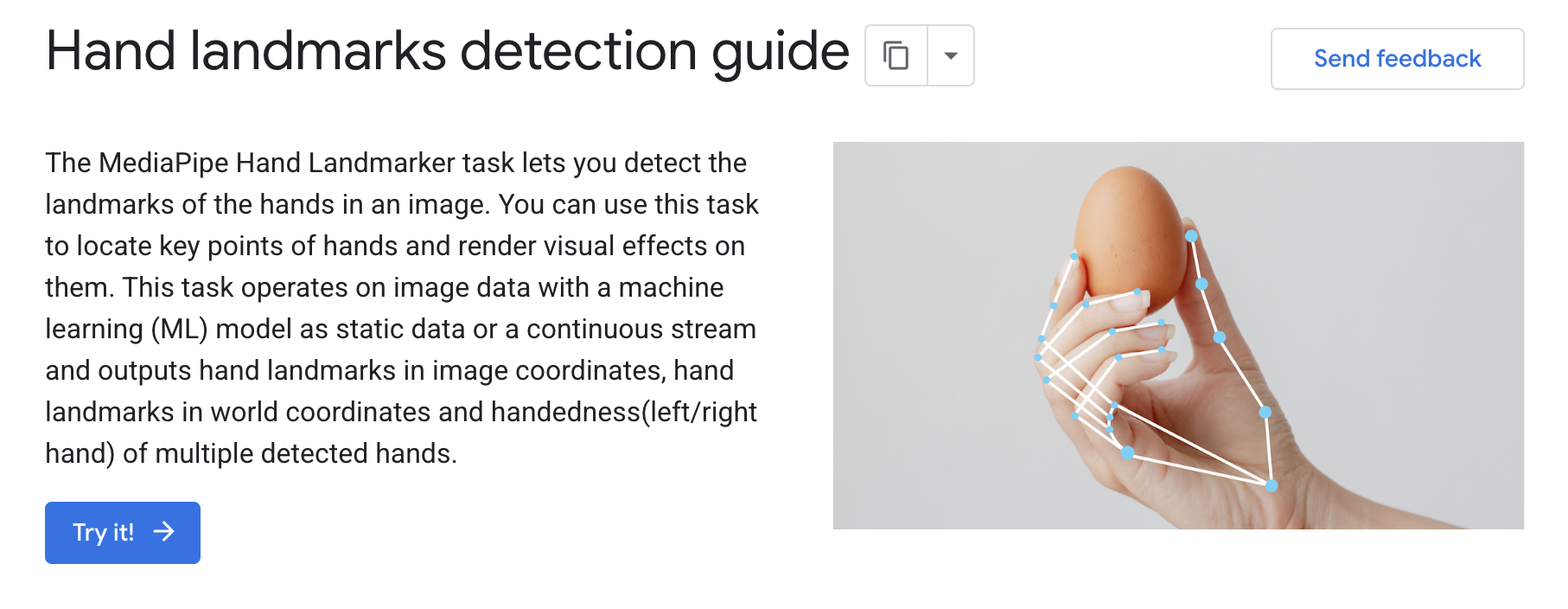

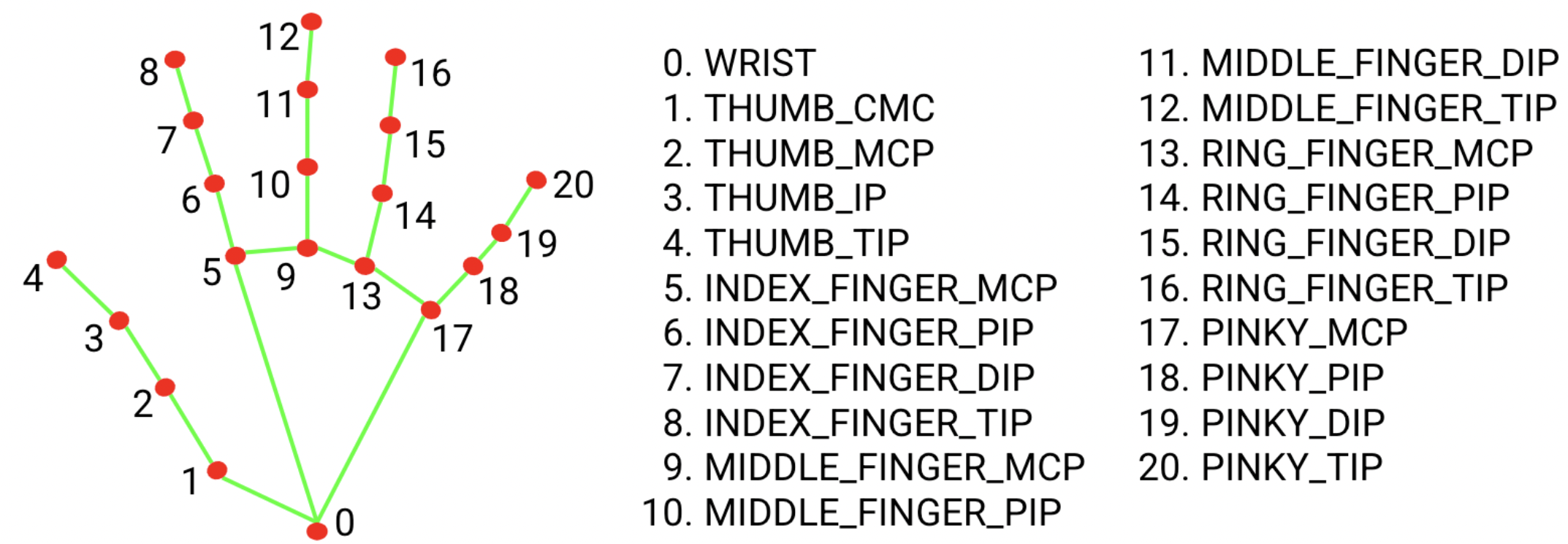

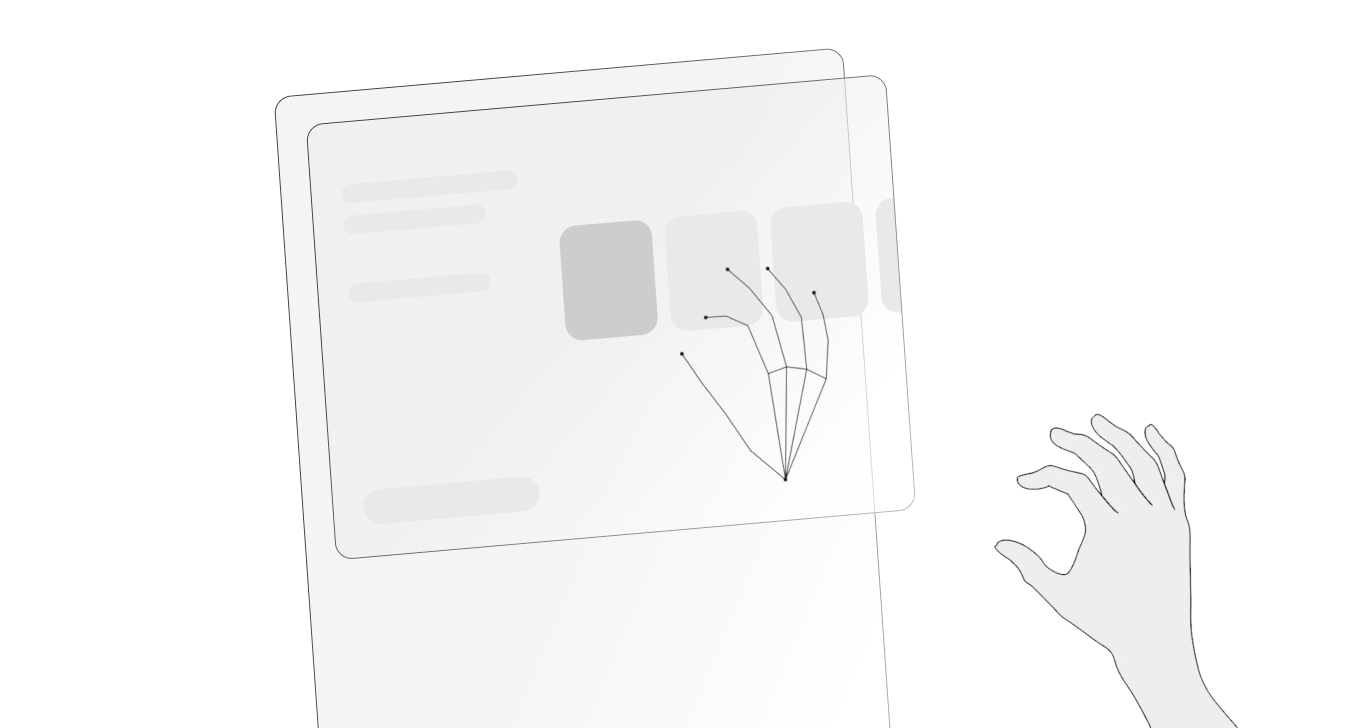

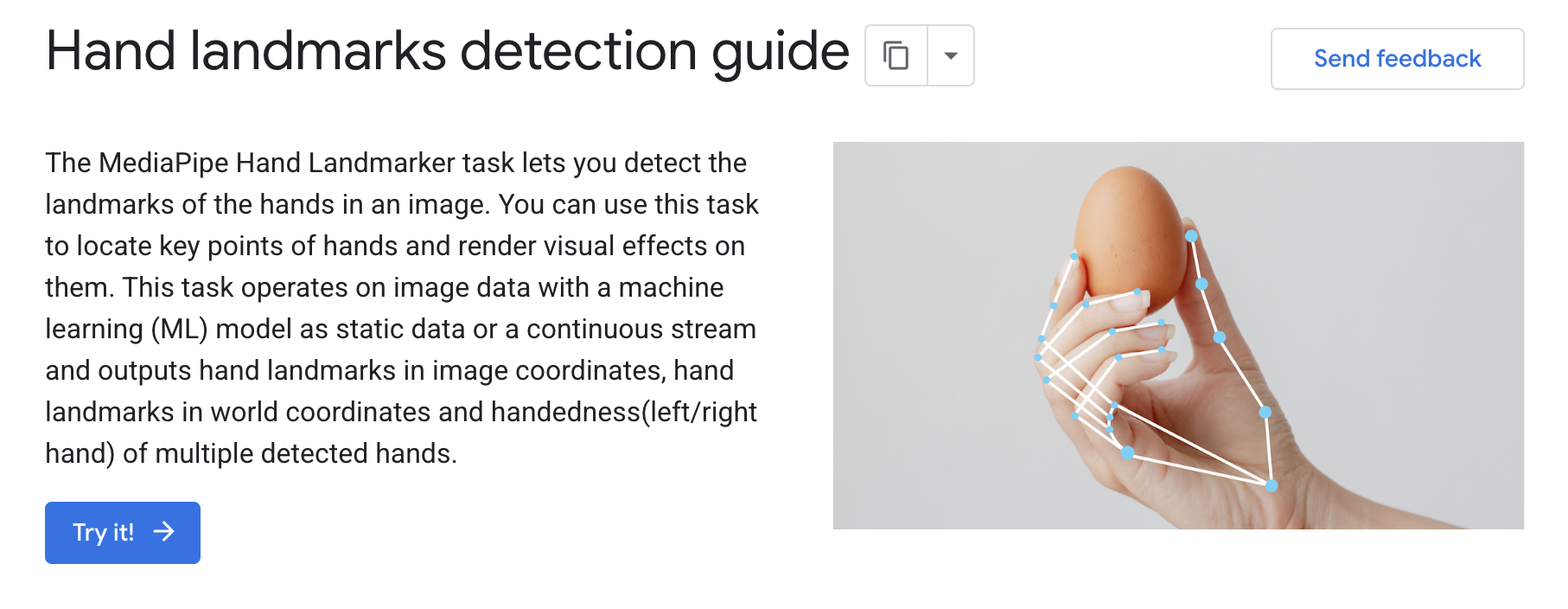

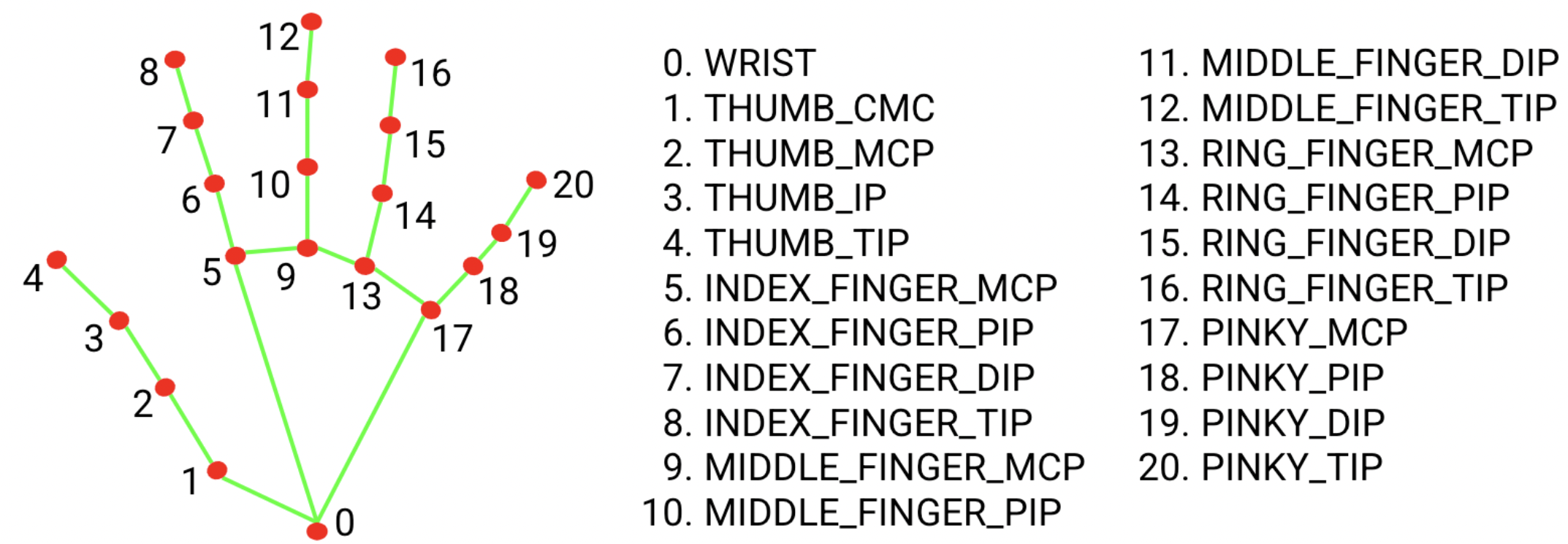

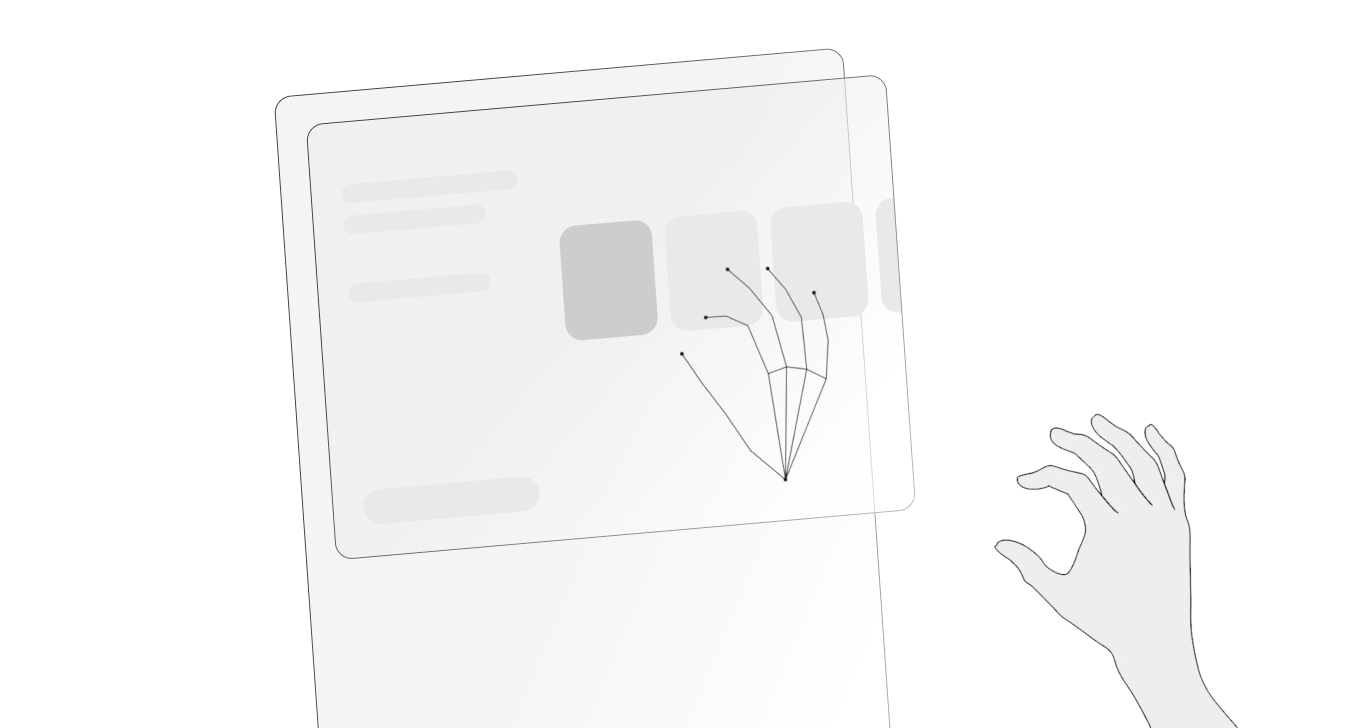

As a support tool for exploring these interactions, I used Google’s MediaPipe Hand Landmarker. This library makes it possible to prototype hand-tracking interactions quickly by visualizing the user’s hand as a real-time skeletal model, enabling immediate experimentation and validation of spatial input techniques.

To address the accessibility challenges faced by wheelchair users at fuel stations, I began by analyzing the specific physical limitations involved in interacting with traditional pump interfaces. This allowed me to identify which actions were most difficult to perform and which elements of the UI contributed to these barriers.

The first step was defining the interaction model

I studied established spatial interface guidelines, selecting only the principles relevant to short, task-oriented interactions such as fuel dispensing or EV charging. Many traditional UI components—like physical or on-screen keyboards—proved unnecessary for these workflows and were therefore excluded to keep the interaction lightweight and accessible.

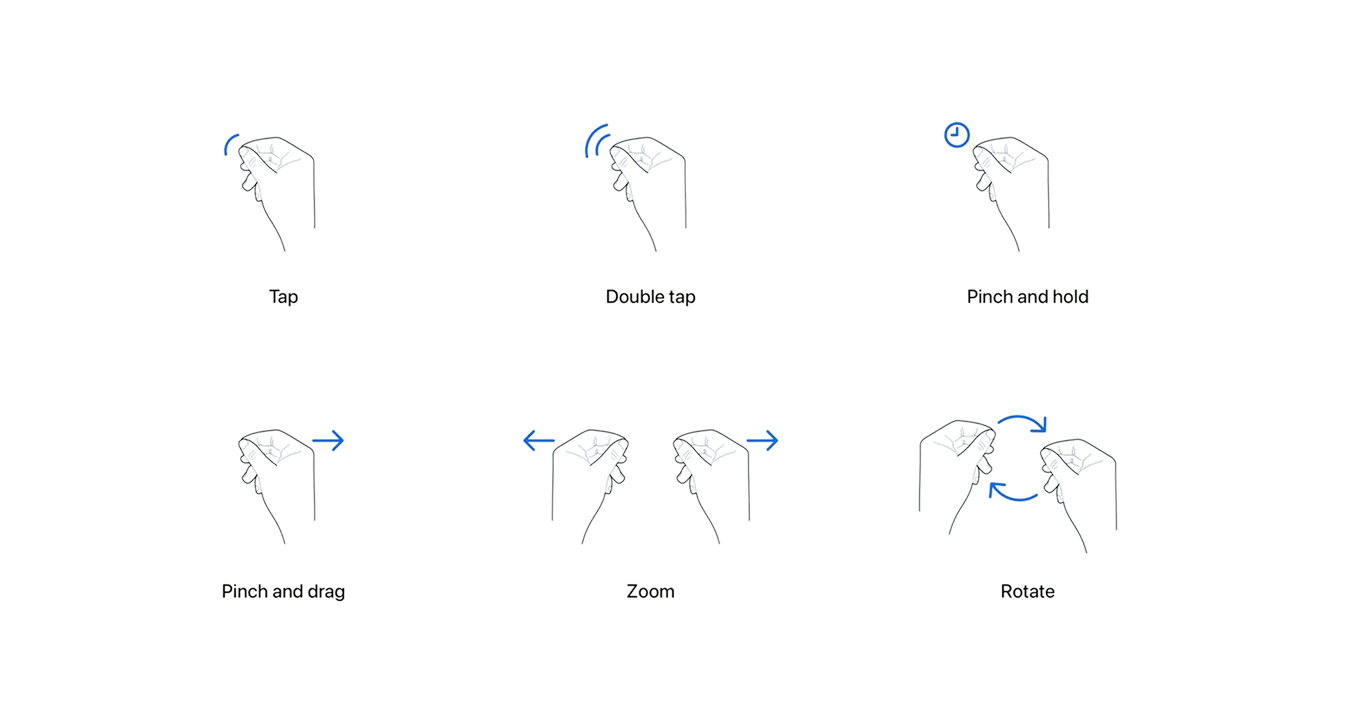

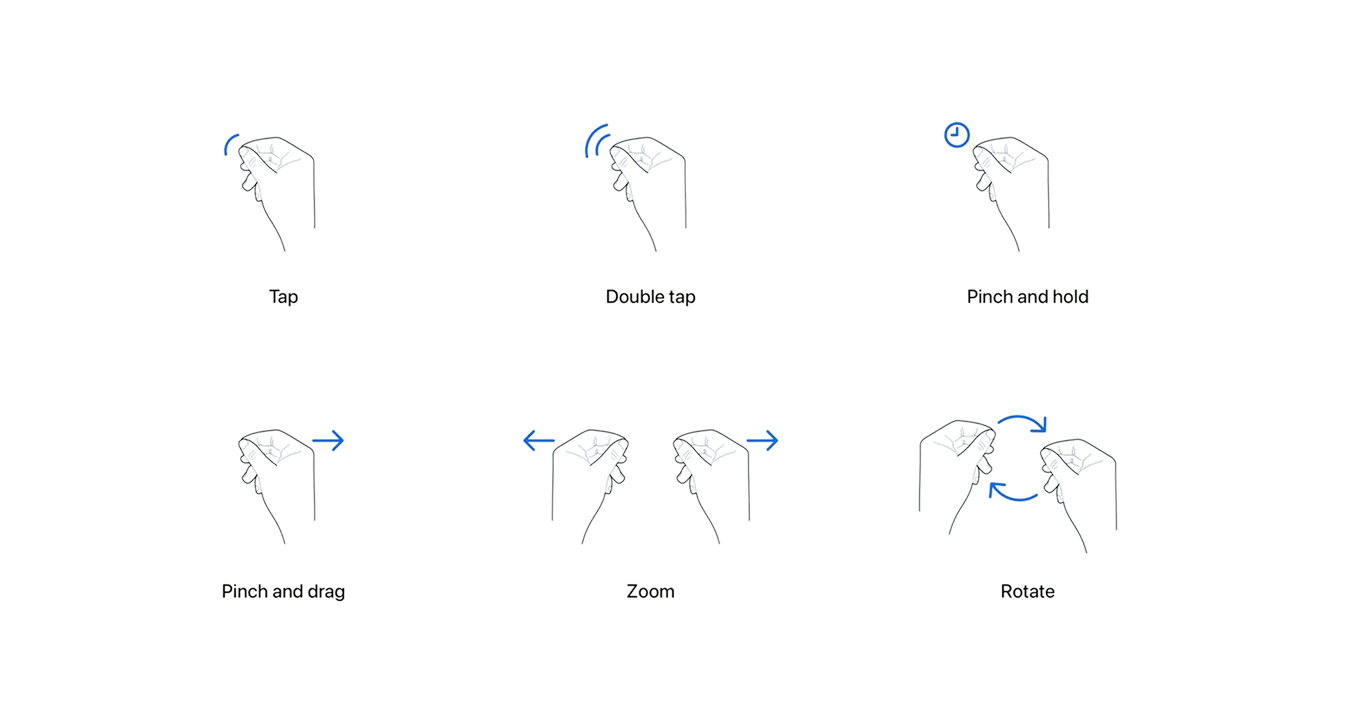

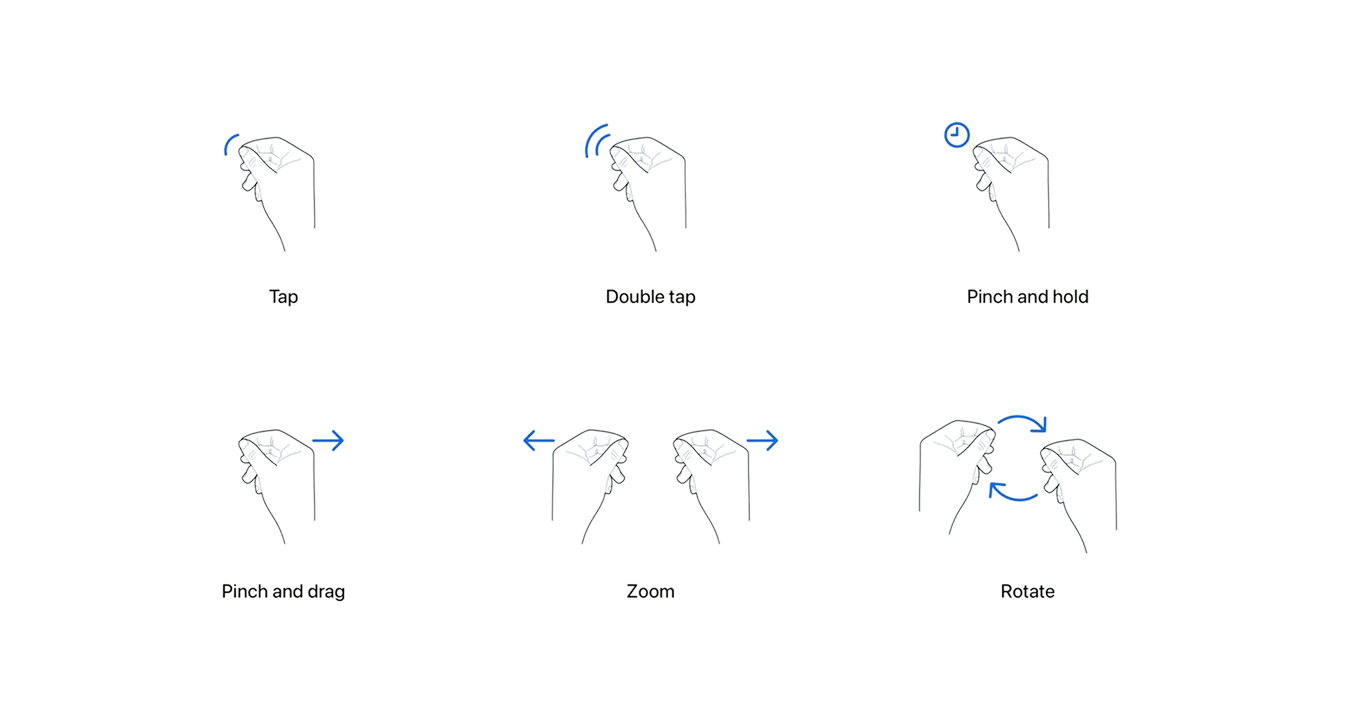

Selecting essential spatial gestures

I mapped spatial gestures to their equivalent touch interactions:

- Pinch → Tap

Used to confirm an action or advance through a step in the flow. - Pinch & Drag → Scroll

The equivalent of dragging on a touchscreen.

Because public service interfaces are usually designed around simple, discrete actions, continuous scrolling is rarely required. For this reason, the pinch-and-drag gesture was considered non-essential and kept only as a secondary option.

The goal is to allow users to move forward and backward through the interface in a simple and intuitive way. In the current system, this is done through small on-screen buttons that require precise tapping. The problem with this approach is that it demands a level of accuracy that can be difficult—especially when interacting with small UI components.

There are certain moments in the flow that require entering textual information on the screen. To address this challenge, I integrated GPT’s speech-to-text APIs, allowing users to input data simply by speaking to the device. This is essential for removing accessibility barriers that would otherwise make these steps impossible for some users.

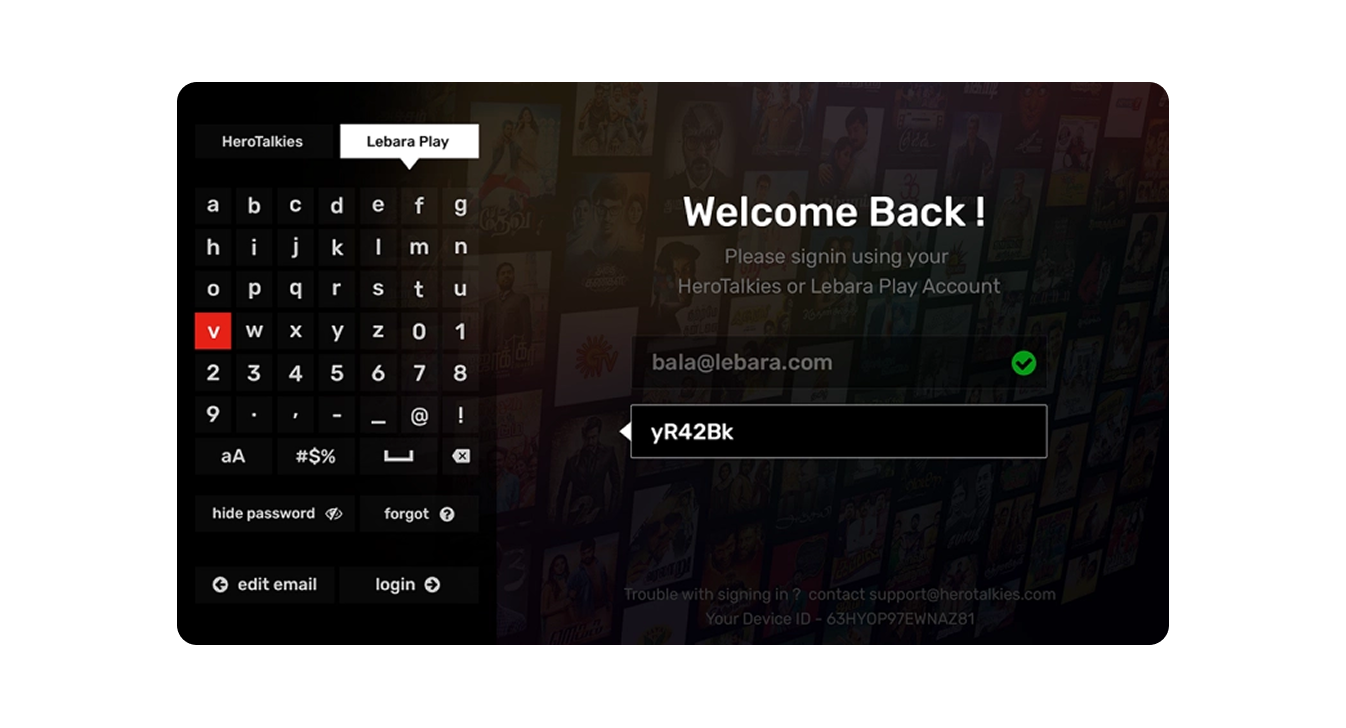

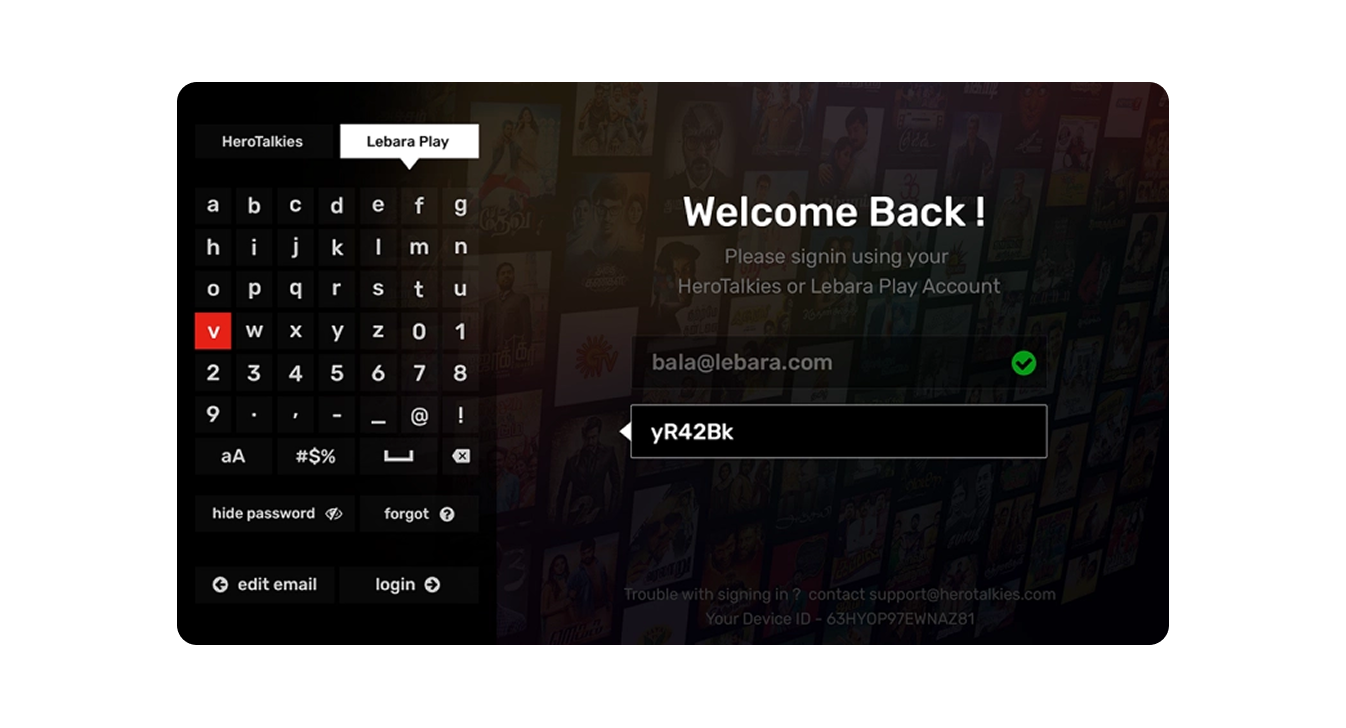

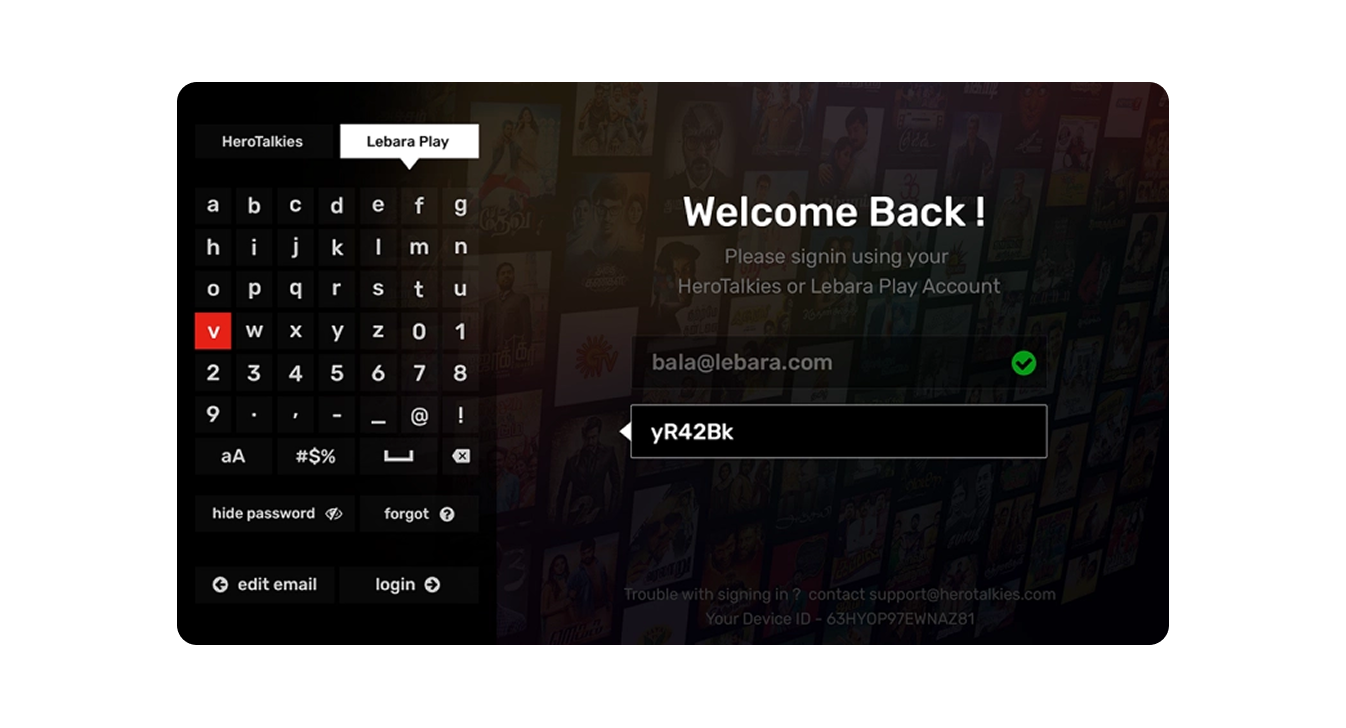

Another alternative is to replicate the simplified on-screen keyboards used by smart TVs (such as Netflix or Prime Video) for search input, which offer a more accessible way to enter short amounts of text without relying on precise touch interactions.

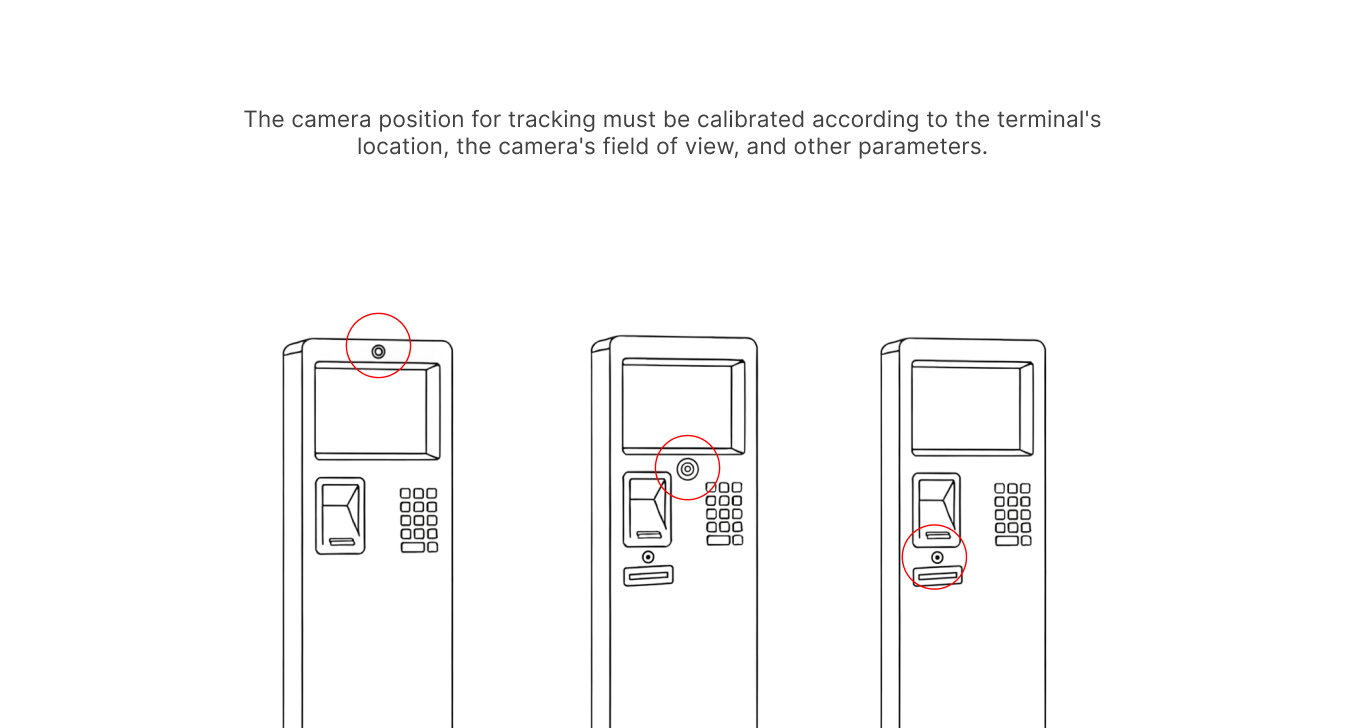

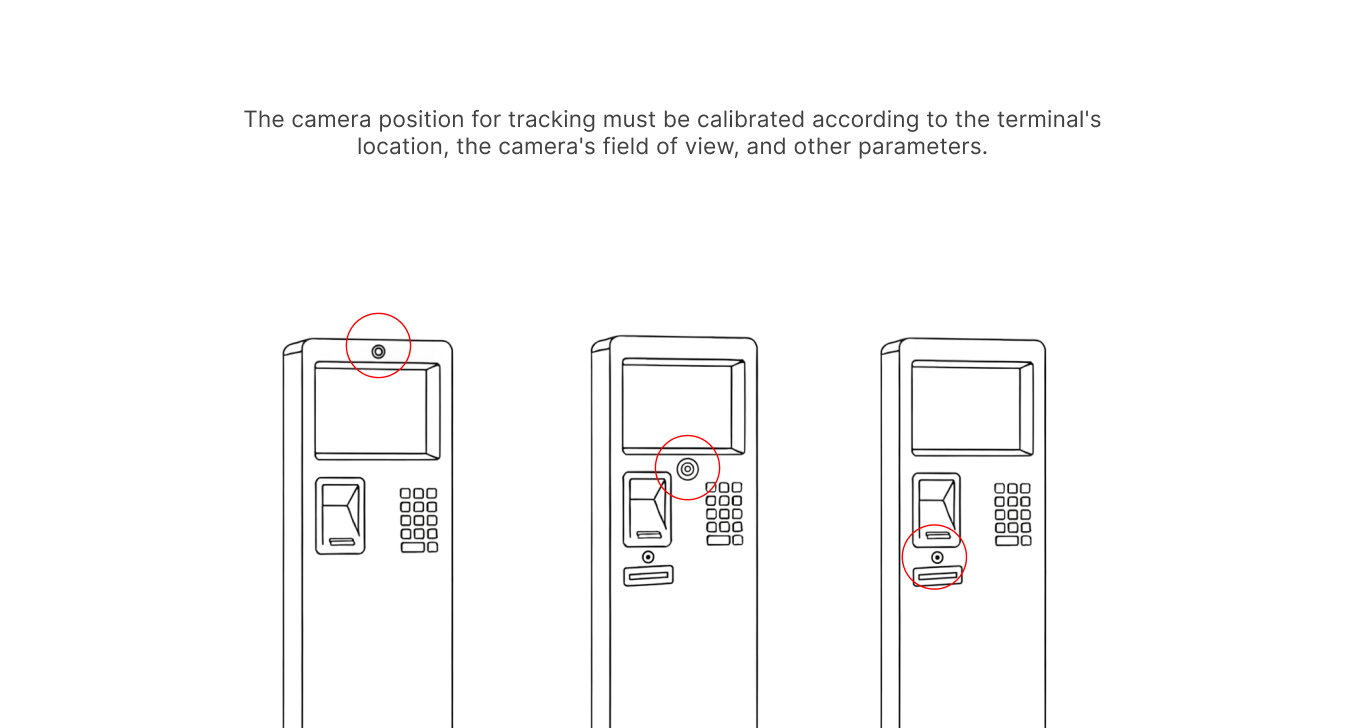

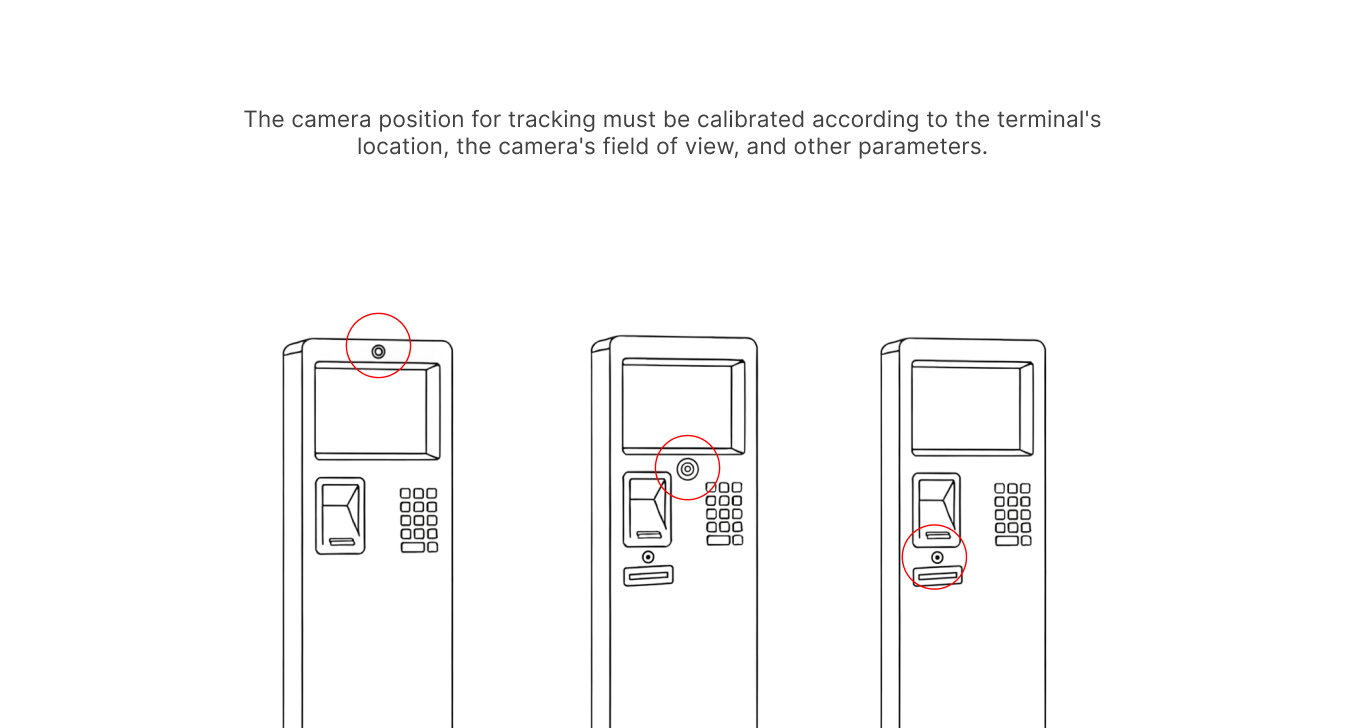

Considerations on camera placement

In this prototype, I do not account for the specific position of the camera, which may vary from one hardware manufacturer to another—or may not be present at all. However, the camera’s placement can significantly influence the accuracy of hand tracking, and different configurations could be optimized accordingly.

From a conceptual standpoint, it is also possible to imagine using an external camera module that can be attached to devices that ship without a built-in front-facing camera. This would allow the spatial interaction layer to be adopted even on older or less advanced hardware.

4 - Output

The development process began in Lovable, where I created a series of prompts to generate the first foundational version of the interface. Using these early prompts, I structured the core building blocks of the system:

- Canvas – the spatial environment where the interface components are placed.

- Hand Skeleton – the real-time hand-tracking model used as the basis for gesture interaction.

- Card Presence – large, easily reachable spatial cards serving as the primary interaction units.

- Minimal Card Interactions – basic pinch-activated actions to navigate forward and backward.

- Calibration – an initial setup step to align the interface to the user’s height and position in the wheelchair.

In the online test version I developed, I added several additional features beyond the minimum requirements for the fuel-station interface. The goal was to experiment freely with more immersive components—such as 3D models, spatial animations, and alternative interaction paradigms—and explore the potential of spatial computing beyond the constraints of traditional public displays.

.gif)

A more human-like 3D hand model

A more advanced phase of the prototype focused on creating a fully-rendered 3D hand model that would precisely follow the movements of the tracked skeletal hand detected by the camera. This allowed for more realistic interaction feedback, better gesture visualization, and a more immersive spatial experience—especially useful when testing gesture recognition accuracy and ergonomics.

.gif)

Complex interactions

Complex interactions—such as separating and merging cards—were refined through precise calibration of the hand skeleton and careful management of spatial depth.

By tuning the depth thresholds and gesture detection sensitivity, I ensured that the interface could reliably distinguish intentional gestures from accidental movements, resulting in smoother, more controlled interactions within the 3D space.

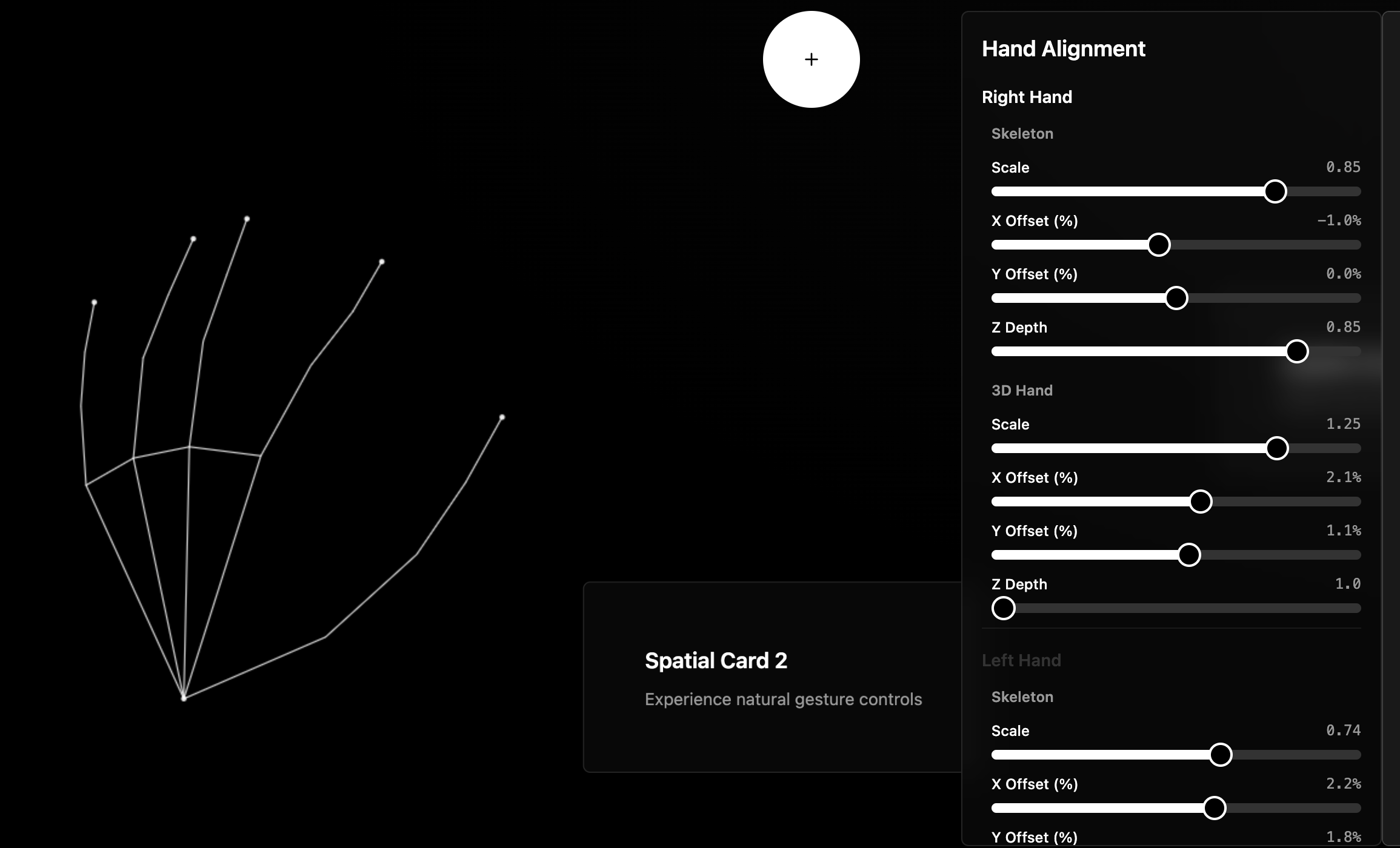

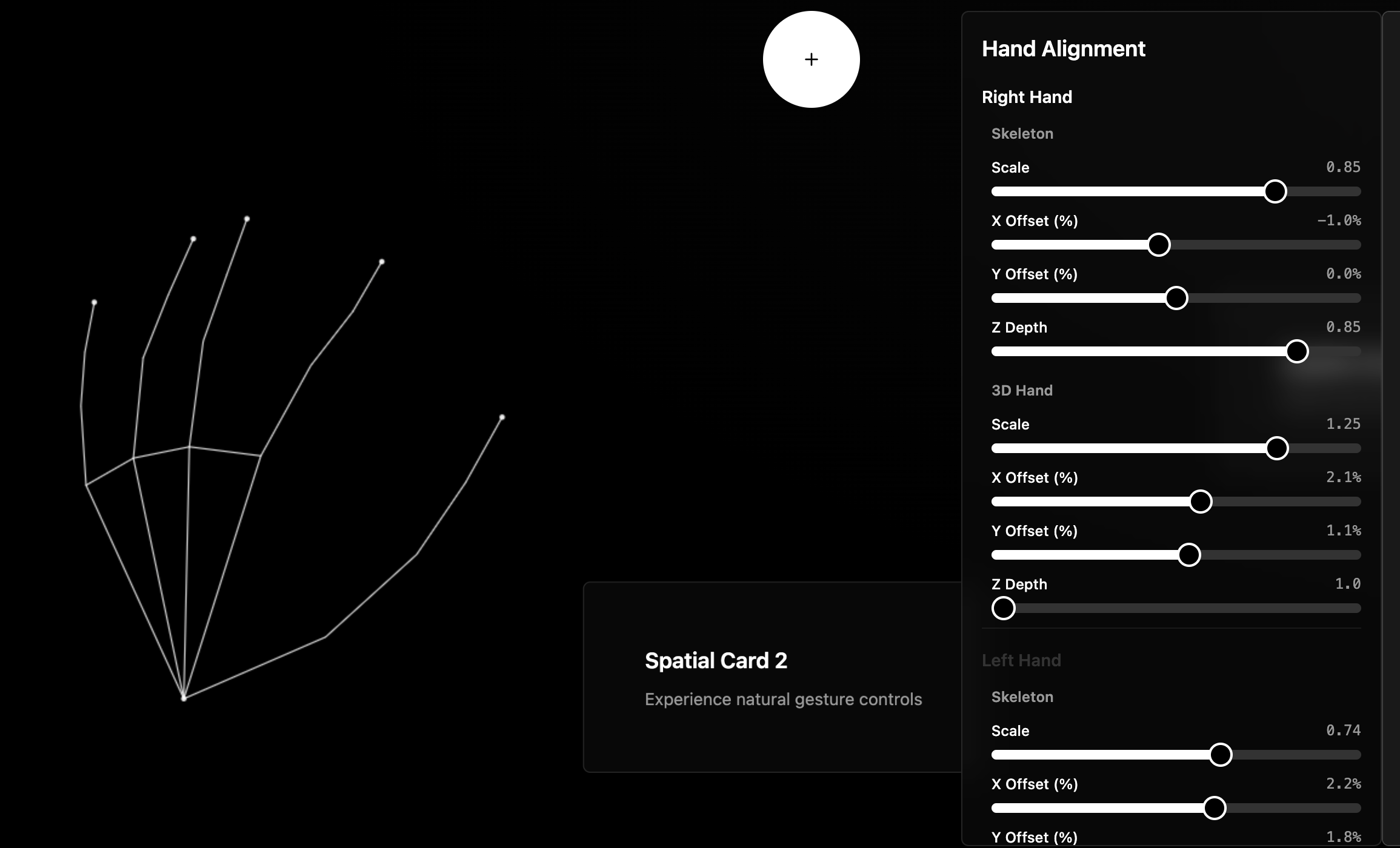

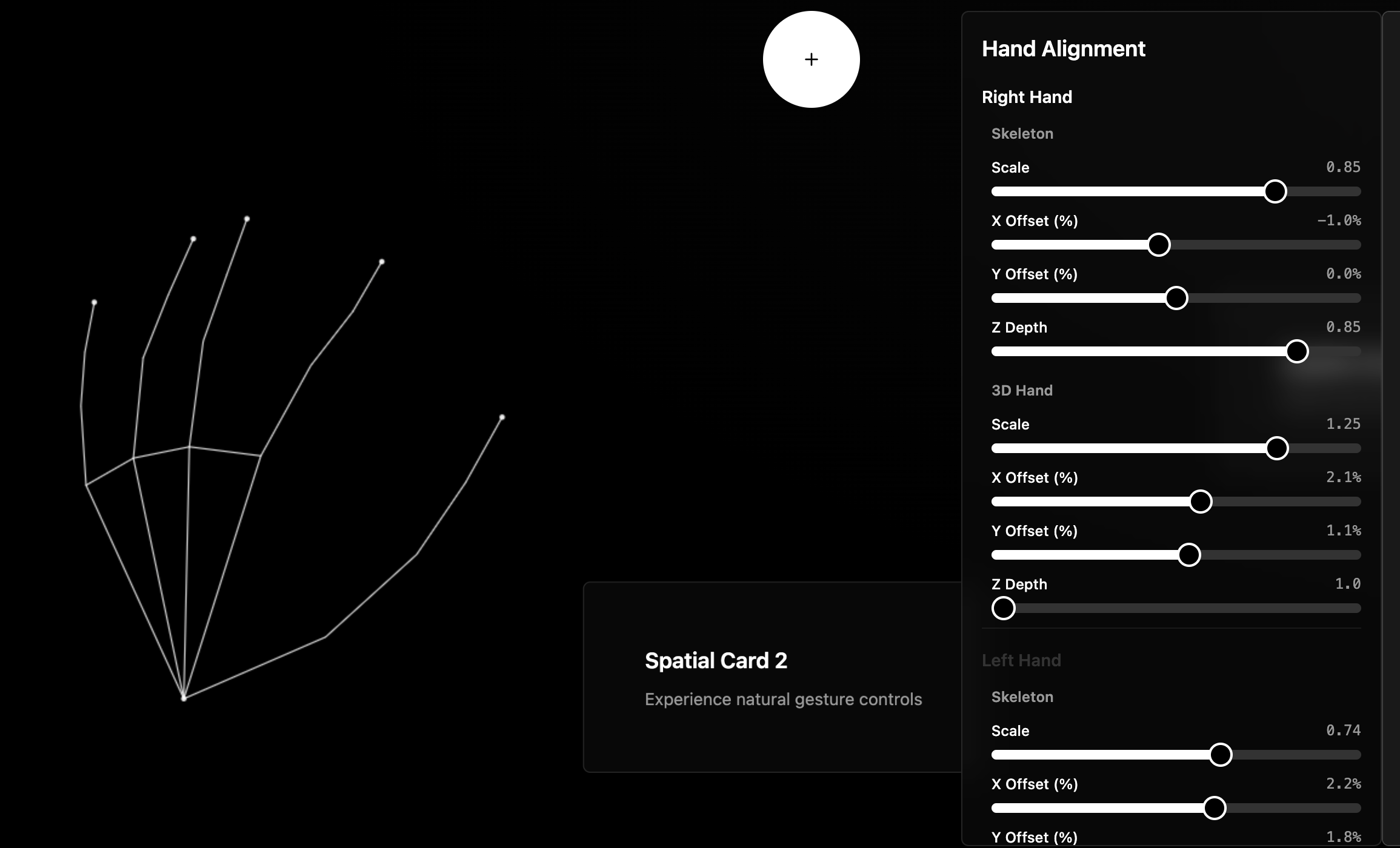

Hand calibration

I then focused on perfecting hand calibration to ensure highly accurate interactions. Since the add-on could be integrated into different devices and environments, the interface needed a calibration step that could reliably adapt to variations in camera position, user height, lighting conditions, and gesture range.

By refining the calibration process, the system is able to correctly align the spatial UI with the user's hand position, guaranteeing consistent gesture detection and a seamless interaction experience across any compatible device.

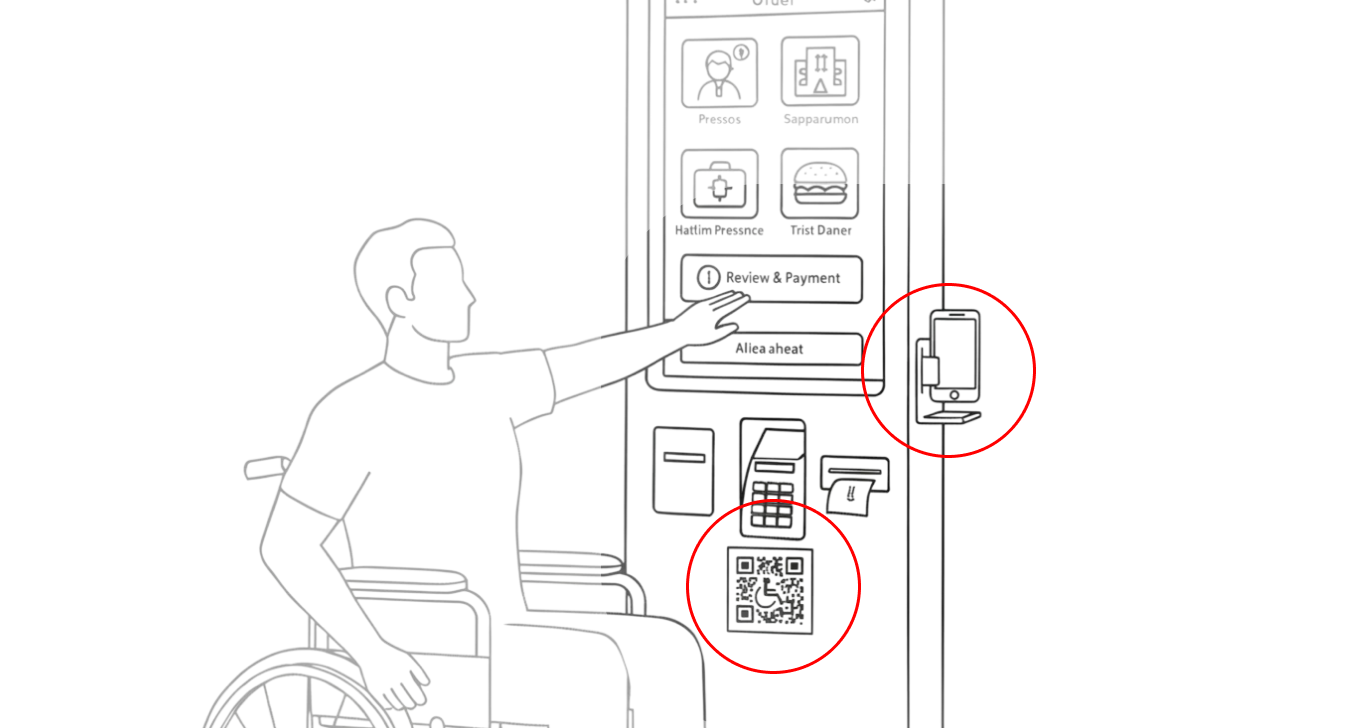

Limitations of hardware

The integration of high-quality cameras into public display hardware is a slow process. Each manufacturer follows its own development cycle, and adding reliable camera modules requires both time and significant investment from suppliers. As a result, relying solely on built-in hardware for hand-tracking is not a scalable or immediately available solution.

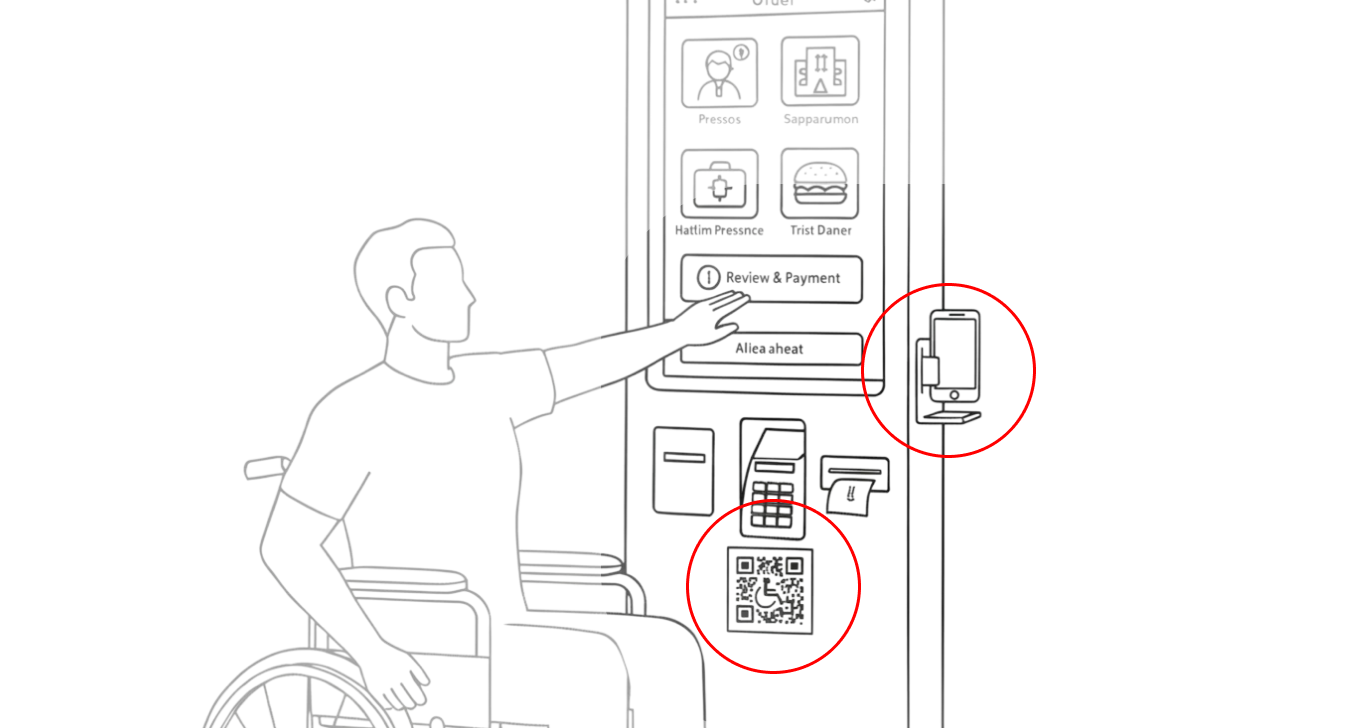

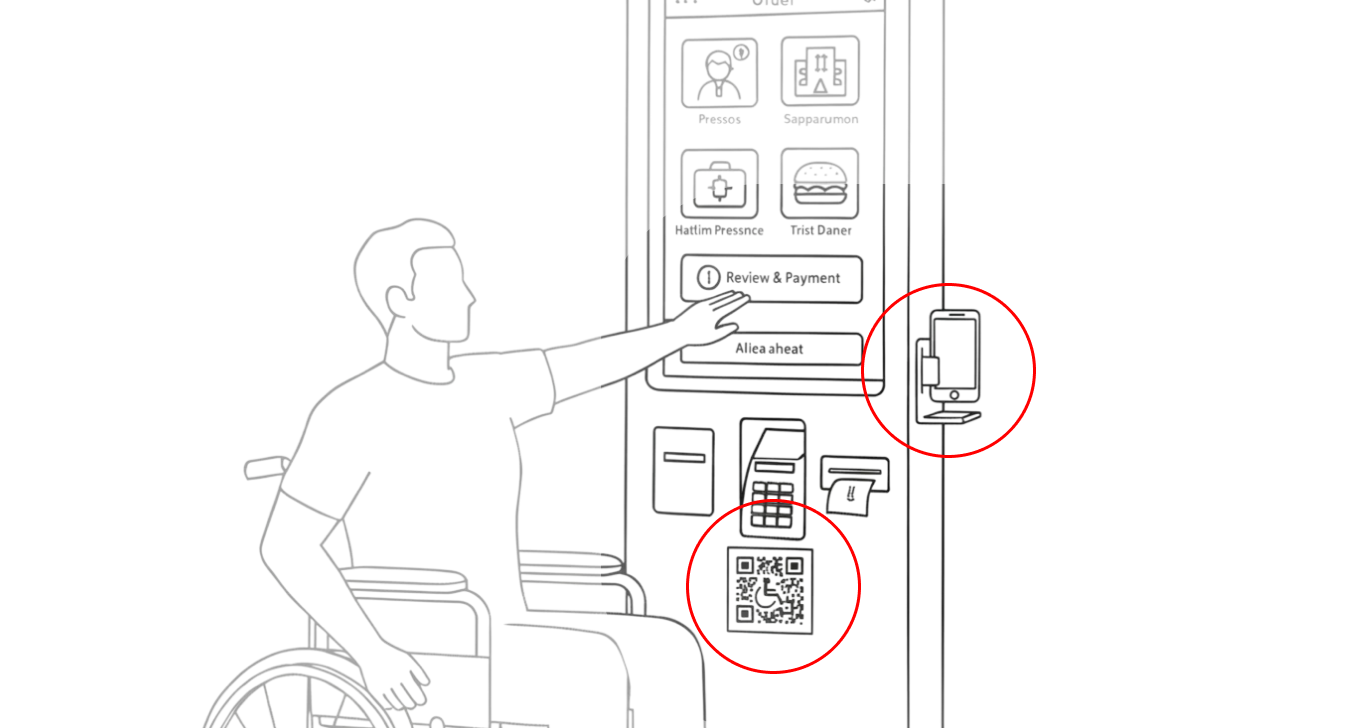

Smartphone live tracking

With this limitation in mind, I envisioned an extended, more advanced version of the software that leverages the user’s smartphone camera instead of the display’s hardware.

After logging in via QR code, the smartphone and the public display would be connected through a secure live streaming link.

From that moment on, users with disabilities could simply position their smartphone to comfortably frame their hand and interact with the interface in real time, without being constrained by the hardware capabilities of the display.

This approach makes the system accessible regardless of the display’s built-in components, offering a flexible and inclusive interaction method that works across different environments and devices.

1 - Context

In the world of fuel stations, accessibility has always been a rather unclear concept for hardware manufacturers. The idea that a person in a wheelchair could refuel their vehicle completely independently—without the assistance of another human being—was considered almost utopian.

From this problem, I decided to explore the field of spatial interfaces and imagine how these tools could be applied to real, everyday issues.

Today, accessibility in physical interfaces often relies on modifying portions of the screen, compressing components or functionalities, and sometimes completely redesigning the software’s UI.

This creates a burden especially for developers, who need additional effort, time, and therefore cost to build a separate version of the software (which often never gets developed) just to accommodate segments of users with disabilities.

People with disabilities can drive, but how many are there?

In the United States, about 65% of people with disabilities drive.

In this case study, I focus on paraplegic individuals rather than quadriplegic ones, since the latter, being unable to use the upper part of their body, are generally not able to operate a vehicle. Paraplegic people, on the other hand, can often maintain a reasonable level of autonomy—when the conditions allow it.

Overall, around 65% of people with disabilities drive a car or other motor vehicle, compared to 88% of people without disabilities. On average, drivers with disabilities drive 5 days a week, while those without disabilities drive 6 days a week.

Can people with paraplegia drive a car?

In a broader national survey conducted in the United States, 36.5% of all individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) drove a modified vehicle, with paraplegia being a significant predictor of driving ability.

The study included a total of 160 participants. Overall, 37% of individuals with SCI drove and owned a modified vehicle.

Nearly half of the people with paraplegia (47%) were drivers, while only 12% of those with tetraplegia drove.

Data Resource: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29288252/

The majority (93%) of drivers were under 60 years old and had a higher level of independence in daily living activities. More drivers (81%) than non-drivers (24%) were employed; drivers also reported better community reintegration and overall quality of life.

The three most common barriers to driving were medical reasons (38%), fear and lack of confidence (17%), and the inability to afford vehicle modifications (13%).

2 - Problem

People with disabilities encounter significant barriers when interacting with public interfaces such as fuel pump displays, ticket machines, ATMs, and self-service kiosks.

These systems are typically designed around the physical reach, posture, and motor capabilities of an able-bodied user—leaving wheelchair users and individuals with reduced upper-body mobility at a clear disadvantage.

This study https://mintviz.usv.ro/publications/2022.UIST.pdf involved eleven participants (nine men, two women), aged between 28 and 59.

65% difficulty reaching the display from the wheelchair

Two primary accessibility challenges emerged for wheelchair users when interacting with public displays:

- Reaching content placed too high on the screen, making it physically difficult or impossible to access.

- Precisely selecting on-screen targets via touch input, due to small touch areas and the precision required.

3 - Approach

To implement the core functionalities, I began by studying the main guidelines for spatial interfaces and extracting only the principles relevant to this specific type of interaction.

Certain traditional components—such as physical or on-screen keyboards—are rarely essential in fuel dispensing or EV charging workflows, and therefore can be omitted in favor of more streamlined interactions.

As a support tool for exploring these interactions, I used Google’s MediaPipe Hand Landmarker. This library makes it possible to prototype hand-tracking interactions quickly by visualizing the user’s hand as a real-time skeletal model, enabling immediate experimentation and validation of spatial input techniques.

To address the accessibility challenges faced by wheelchair users at fuel stations, I began by analyzing the specific physical limitations involved in interacting with traditional pump interfaces. This allowed me to identify which actions were most difficult to perform and which elements of the UI contributed to these barriers.

The first step was defining the interaction model

I studied established spatial interface guidelines, selecting only the principles relevant to short, task-oriented interactions such as fuel dispensing or EV charging. Many traditional UI components—like physical or on-screen keyboards—proved unnecessary for these workflows and were therefore excluded to keep the interaction lightweight and accessible.

Selecting essential spatial gestures

I mapped spatial gestures to their equivalent touch interactions:

- Pinch → Tap

Used to confirm an action or advance through a step in the flow. - Pinch & Drag → Scroll

The equivalent of dragging on a touchscreen.

Because public service interfaces are usually designed around simple, discrete actions, continuous scrolling is rarely required. For this reason, the pinch-and-drag gesture was considered non-essential and kept only as a secondary option.

The goal is to allow users to move forward and backward through the interface in a simple and intuitive way. In the current system, this is done through small on-screen buttons that require precise tapping. The problem with this approach is that it demands a level of accuracy that can be difficult—especially when interacting with small UI components.

There are certain moments in the flow that require entering textual information on the screen. To address this challenge, I integrated GPT’s speech-to-text APIs, allowing users to input data simply by speaking to the device. This is essential for removing accessibility barriers that would otherwise make these steps impossible for some users.

Another alternative is to replicate the simplified on-screen keyboards used by smart TVs (such as Netflix or Prime Video) for search input, which offer a more accessible way to enter short amounts of text without relying on precise touch interactions.

Considerations on camera placement

In this prototype, I do not account for the specific position of the camera, which may vary from one hardware manufacturer to another—or may not be present at all. However, the camera’s placement can significantly influence the accuracy of hand tracking, and different configurations could be optimized accordingly.

From a conceptual standpoint, it is also possible to imagine using an external camera module that can be attached to devices that ship without a built-in front-facing camera. This would allow the spatial interaction layer to be adopted even on older or less advanced hardware.

4 - Output

The development process began in Lovable, where I created a series of prompts to generate the first foundational version of the interface. Using these early prompts, I structured the core building blocks of the system:

- Canvas – the spatial environment where the interface components are placed.

- Hand Skeleton – the real-time hand-tracking model used as the basis for gesture interaction.

- Card Presence – large, easily reachable spatial cards serving as the primary interaction units.

- Minimal Card Interactions – basic pinch-activated actions to navigate forward and backward.

- Calibration – an initial setup step to align the interface to the user’s height and position in the wheelchair.

In the online test version I developed, I added several additional features beyond the minimum requirements for the fuel-station interface. The goal was to experiment freely with more immersive components—such as 3D models, spatial animations, and alternative interaction paradigms—and explore the potential of spatial computing beyond the constraints of traditional public displays.

.gif)

A more human-like 3D hand model

A more advanced phase of the prototype focused on creating a fully-rendered 3D hand model that would precisely follow the movements of the tracked skeletal hand detected by the camera. This allowed for more realistic interaction feedback, better gesture visualization, and a more immersive spatial experience—especially useful when testing gesture recognition accuracy and ergonomics.

.gif)

Complex interactions

Complex interactions—such as separating and merging cards—were refined through precise calibration of the hand skeleton and careful management of spatial depth.

By tuning the depth thresholds and gesture detection sensitivity, I ensured that the interface could reliably distinguish intentional gestures from accidental movements, resulting in smoother, more controlled interactions within the 3D space.

Hand calibration

I then focused on perfecting hand calibration to ensure highly accurate interactions. Since the add-on could be integrated into different devices and environments, the interface needed a calibration step that could reliably adapt to variations in camera position, user height, lighting conditions, and gesture range.

By refining the calibration process, the system is able to correctly align the spatial UI with the user's hand position, guaranteeing consistent gesture detection and a seamless interaction experience across any compatible device.

Limitations of hardware

The integration of high-quality cameras into public display hardware is a slow process. Each manufacturer follows its own development cycle, and adding reliable camera modules requires both time and significant investment from suppliers. As a result, relying solely on built-in hardware for hand-tracking is not a scalable or immediately available solution.

Smartphone live tracking

With this limitation in mind, I envisioned an extended, more advanced version of the software that leverages the user’s smartphone camera instead of the display’s hardware.

After logging in via QR code, the smartphone and the public display would be connected through a secure live streaming link.

From that moment on, users with disabilities could simply position their smartphone to comfortably frame their hand and interact with the interface in real time, without being constrained by the hardware capabilities of the display.

This approach makes the system accessible regardless of the display’s built-in components, offering a flexible and inclusive interaction method that works across different environments and devices.

Outcome

Results (qualitative and quantitative)

- Improved interaction conditions:

Prior to this solution, accessibility relied on shrinking or rearranging UI components on the physical display. However, physical constraints—such as the distance between the wheelchair and the screen—remained unsolved.

With this spatial interface, users can interact with the system even from a greater distance, removing the need for precise touch interaction and eliminating reachability issues.

- Usability metrics:

Quantitative evaluation is still in progress, but early testing shows that gesture-based navigation reduces physical effort and minimizes interaction errors caused by limited arm mobility.

Impact on user experience

- Increased autonomy and ease of use:

(To be validated with real users)

The system is designed to let wheelchair users complete the entire flow without relying on physical contact, significantly reducing effort and friction.

- Barriers removed or reduced:

The key barrier addressed is the physical distance between the user and the display, as well as the difficulty of interacting with small on-screen touch targets.

I initially thought that difficulty seeing the content on the screen would have a much greater impact on the experience, but it turned out to affect only a small percentage of users. This led me to reconsider the solution as more feasible.

Business value

We consider 150,000 fuel stations, 41 million people with disabilities, 26 million people who drive, and an average annual fuel expenditure of 2,624 dollars. Assuming that between 20% and 40% of people with disabilities are drivers, we obtain between 8.2 million (41M × 0.20) and 16.4 million (41M × 0.40) disabled drivers, representing an annual fuel market worth between 21.5 billion (8.2M × 2,624 $) and 43 billion dollars (16.4M × 2,624 $).

Using the intermediate scenario (30%), the number becomes 12.3 million drivers with disabilities.

If between 0.5% and 2% of these 12.3 million drivers chose accessible stations, this would correspond to 61,500 (12.3M × 0.005), 123,000 (× 0.01), or 246,000 (× 0.02) new customers distributed across all 150,000 stations. Divided per station, this results in 0.41, 0.82, and 1.64 additional customers respectively. Multiplying by the annual spending of 2,624 dollars, a station would gain approximately 1,076 $, 2,152 $, or 4,304 $ per year.

Relative to an estimated average annual station revenue of 1.5 million dollars, these increases correspond to a growth between approximately 0.07% (1,076 / 1,500,000) and 0.28% (4,304 / 1,500,000).

Even without formal KPIs, the concept suggests several potential benefits:

- Reduced long-term technical complexity, since spatial interaction works as an additional layer instead of requiring separate accessible UI versions.

- Lower maintenance and development costs, as developers can maintain a single software interface rather than duplicating or redesigning it for accessibility needs.

- Improved brand perception, thanks to a more inclusive, forward-thinking interaction model that demonstrates commitment to accessibility and innovation.

Validation of the concept

Full validation requires testing the prototype directly in a fuel-station environment with wheelchair users, replicating the exact conditions of interacting with a real pump interface.

The same approach can also be tested on other public terminals, such as ticket machines, ATMs, or EV charging stations, as the interaction model is hardware-agnostic.

1 - Context

In the world of fuel stations, accessibility has always been a rather unclear concept for hardware manufacturers. The idea that a person in a wheelchair could refuel their vehicle completely independently—without the assistance of another human being—was considered almost utopian.

From this problem, I decided to explore the field of spatial interfaces and imagine how these tools could be applied to real, everyday issues.

Today, accessibility in physical interfaces often relies on modifying portions of the screen, compressing components or functionalities, and sometimes completely redesigning the software’s UI.

This creates a burden especially for developers, who need additional effort, time, and therefore cost to build a separate version of the software (which often never gets developed) just to accommodate segments of users with disabilities.

People with disabilities can drive, but how many are there?

In the United States, about 65% of people with disabilities drive.

In this case study, I focus on paraplegic individuals rather than quadriplegic ones, since the latter, being unable to use the upper part of their body, are generally not able to operate a vehicle. Paraplegic people, on the other hand, can often maintain a reasonable level of autonomy—when the conditions allow it.

Overall, around 65% of people with disabilities drive a car or other motor vehicle, compared to 88% of people without disabilities. On average, drivers with disabilities drive 5 days a week, while those without disabilities drive 6 days a week.

Can people with paraplegia drive a car?

In a broader national survey conducted in the United States, 36.5% of all individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) drove a modified vehicle, with paraplegia being a significant predictor of driving ability.

The study included a total of 160 participants. Overall, 37% of individuals with SCI drove and owned a modified vehicle.

Nearly half of the people with paraplegia (47%) were drivers, while only 12% of those with tetraplegia drove.

Data Resource: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29288252/

The majority (93%) of drivers were under 60 years old and had a higher level of independence in daily living activities. More drivers (81%) than non-drivers (24%) were employed; drivers also reported better community reintegration and overall quality of life.

The three most common barriers to driving were medical reasons (38%), fear and lack of confidence (17%), and the inability to afford vehicle modifications (13%).

2 - Problem

People with disabilities encounter significant barriers when interacting with public interfaces such as fuel pump displays, ticket machines, ATMs, and self-service kiosks.

These systems are typically designed around the physical reach, posture, and motor capabilities of an able-bodied user—leaving wheelchair users and individuals with reduced upper-body mobility at a clear disadvantage.

This study https://mintviz.usv.ro/publications/2022.UIST.pdf involved eleven participants (nine men, two women), aged between 28 and 59.

65% difficulty reaching the display from the wheelchair

Two primary accessibility challenges emerged for wheelchair users when interacting with public displays:

- Reaching content placed too high on the screen, making it physically difficult or impossible to access.

- Precisely selecting on-screen targets via touch input, due to small touch areas and the precision required.

3 - Approach

To implement the core functionalities, I began by studying the main guidelines for spatial interfaces and extracting only the principles relevant to this specific type of interaction.

Certain traditional components—such as physical or on-screen keyboards—are rarely essential in fuel dispensing or EV charging workflows, and therefore can be omitted in favor of more streamlined interactions.

As a support tool for exploring these interactions, I used Google’s MediaPipe Hand Landmarker. This library makes it possible to prototype hand-tracking interactions quickly by visualizing the user’s hand as a real-time skeletal model, enabling immediate experimentation and validation of spatial input techniques.

To address the accessibility challenges faced by wheelchair users at fuel stations, I began by analyzing the specific physical limitations involved in interacting with traditional pump interfaces. This allowed me to identify which actions were most difficult to perform and which elements of the UI contributed to these barriers.

The first step was defining the interaction model

I studied established spatial interface guidelines, selecting only the principles relevant to short, task-oriented interactions such as fuel dispensing or EV charging. Many traditional UI components—like physical or on-screen keyboards—proved unnecessary for these workflows and were therefore excluded to keep the interaction lightweight and accessible.

Selecting essential spatial gestures

I mapped spatial gestures to their equivalent touch interactions:

- Pinch → Tap

Used to confirm an action or advance through a step in the flow. - Pinch & Drag → Scroll

The equivalent of dragging on a touchscreen.

Because public service interfaces are usually designed around simple, discrete actions, continuous scrolling is rarely required. For this reason, the pinch-and-drag gesture was considered non-essential and kept only as a secondary option.

The goal is to allow users to move forward and backward through the interface in a simple and intuitive way. In the current system, this is done through small on-screen buttons that require precise tapping. The problem with this approach is that it demands a level of accuracy that can be difficult—especially when interacting with small UI components.

There are certain moments in the flow that require entering textual information on the screen. To address this challenge, I integrated GPT’s speech-to-text APIs, allowing users to input data simply by speaking to the device. This is essential for removing accessibility barriers that would otherwise make these steps impossible for some users.

Another alternative is to replicate the simplified on-screen keyboards used by smart TVs (such as Netflix or Prime Video) for search input, which offer a more accessible way to enter short amounts of text without relying on precise touch interactions.

Considerations on camera placement

In this prototype, I do not account for the specific position of the camera, which may vary from one hardware manufacturer to another—or may not be present at all. However, the camera’s placement can significantly influence the accuracy of hand tracking, and different configurations could be optimized accordingly.

From a conceptual standpoint, it is also possible to imagine using an external camera module that can be attached to devices that ship without a built-in front-facing camera. This would allow the spatial interaction layer to be adopted even on older or less advanced hardware.

4 - Output

The development process began in Lovable, where I created a series of prompts to generate the first foundational version of the interface. Using these early prompts, I structured the core building blocks of the system:

- Canvas – the spatial environment where the interface components are placed.

- Hand Skeleton – the real-time hand-tracking model used as the basis for gesture interaction.

- Card Presence – large, easily reachable spatial cards serving as the primary interaction units.

- Minimal Card Interactions – basic pinch-activated actions to navigate forward and backward.

- Calibration – an initial setup step to align the interface to the user’s height and position in the wheelchair.

In the online test version I developed, I added several additional features beyond the minimum requirements for the fuel-station interface. The goal was to experiment freely with more immersive components—such as 3D models, spatial animations, and alternative interaction paradigms—and explore the potential of spatial computing beyond the constraints of traditional public displays.

.gif)

A more human-like 3D hand model

A more advanced phase of the prototype focused on creating a fully-rendered 3D hand model that would precisely follow the movements of the tracked skeletal hand detected by the camera. This allowed for more realistic interaction feedback, better gesture visualization, and a more immersive spatial experience—especially useful when testing gesture recognition accuracy and ergonomics.

.gif)

Complex interactions

Complex interactions—such as separating and merging cards—were refined through precise calibration of the hand skeleton and careful management of spatial depth.

By tuning the depth thresholds and gesture detection sensitivity, I ensured that the interface could reliably distinguish intentional gestures from accidental movements, resulting in smoother, more controlled interactions within the 3D space.

Hand calibration

I then focused on perfecting hand calibration to ensure highly accurate interactions. Since the add-on could be integrated into different devices and environments, the interface needed a calibration step that could reliably adapt to variations in camera position, user height, lighting conditions, and gesture range.

By refining the calibration process, the system is able to correctly align the spatial UI with the user's hand position, guaranteeing consistent gesture detection and a seamless interaction experience across any compatible device.

Limitations of hardware

The integration of high-quality cameras into public display hardware is a slow process. Each manufacturer follows its own development cycle, and adding reliable camera modules requires both time and significant investment from suppliers. As a result, relying solely on built-in hardware for hand-tracking is not a scalable or immediately available solution.

Smartphone live tracking

With this limitation in mind, I envisioned an extended, more advanced version of the software that leverages the user’s smartphone camera instead of the display’s hardware.

After logging in via QR code, the smartphone and the public display would be connected through a secure live streaming link.

From that moment on, users with disabilities could simply position their smartphone to comfortably frame their hand and interact with the interface in real time, without being constrained by the hardware capabilities of the display.

This approach makes the system accessible regardless of the display’s built-in components, offering a flexible and inclusive interaction method that works across different environments and devices.